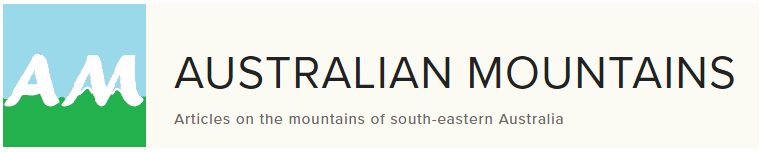

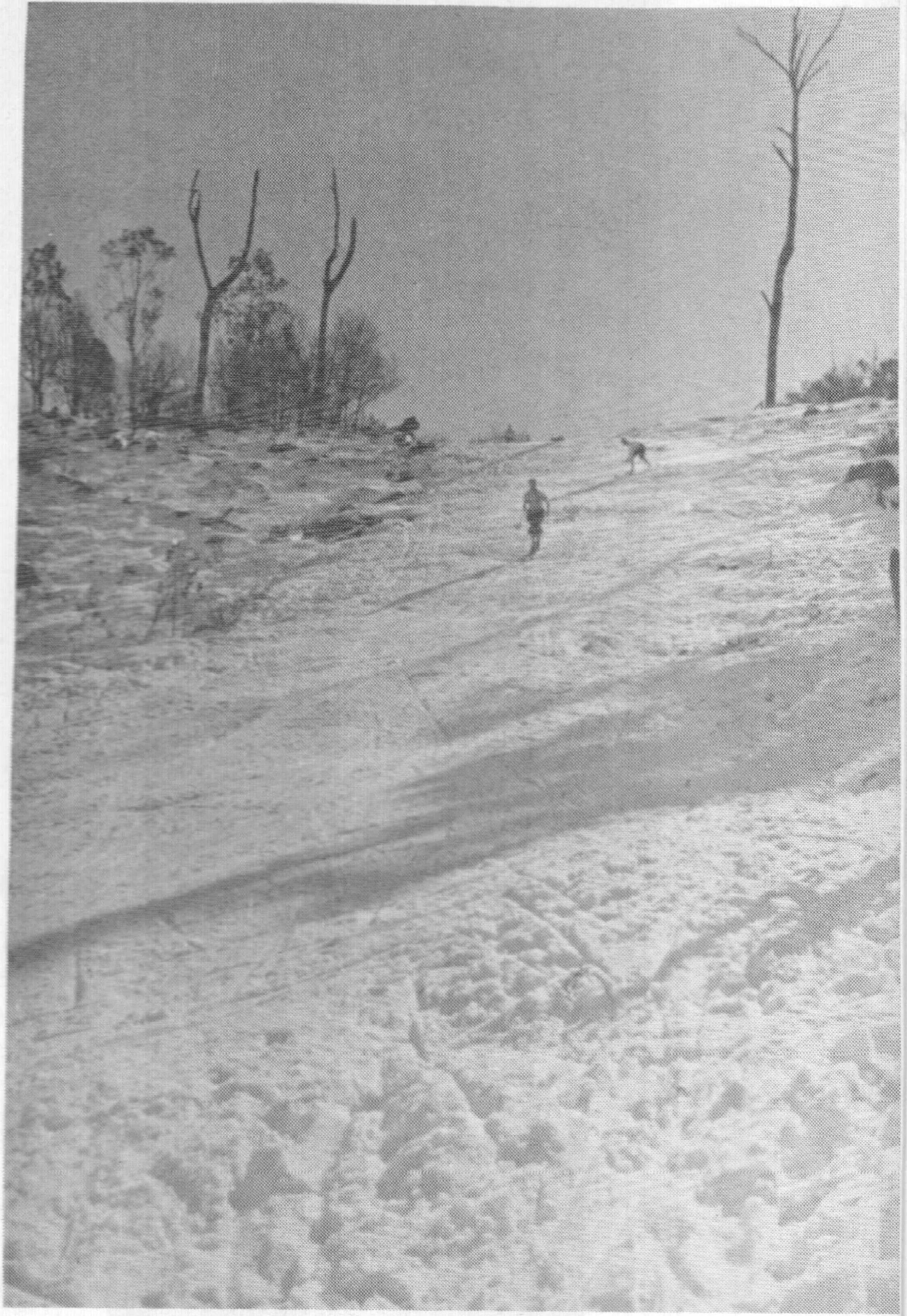

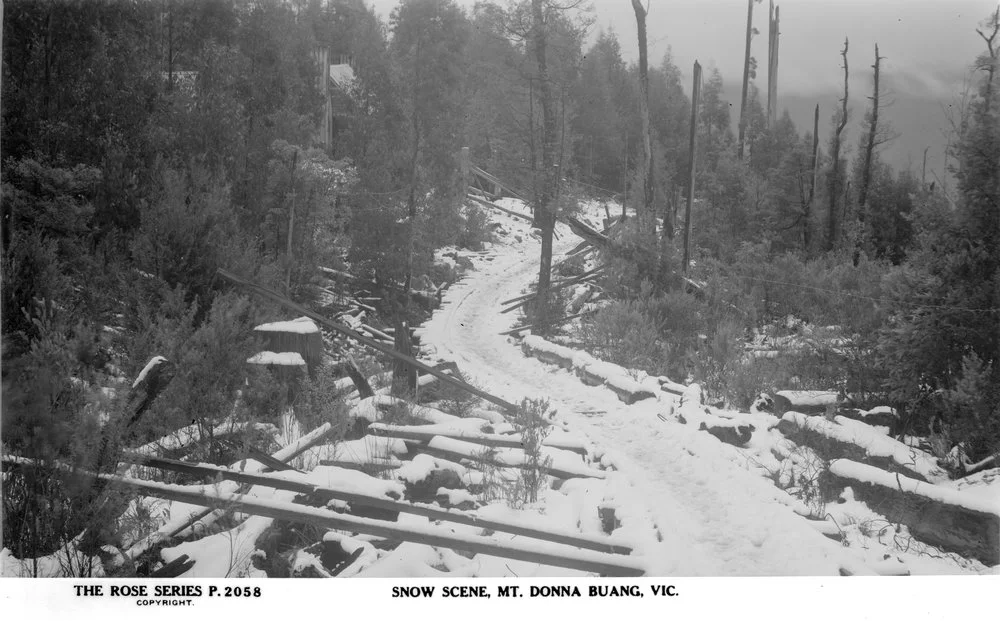

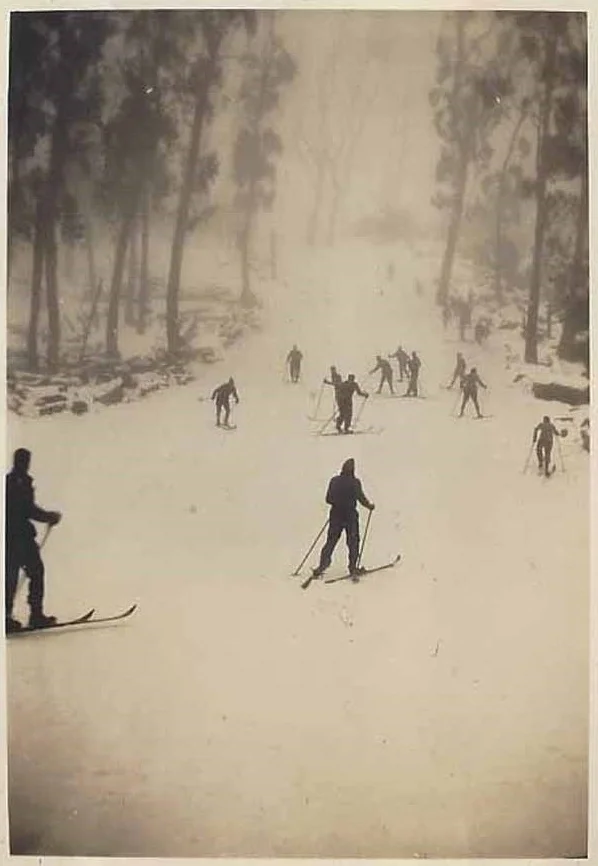

The Main Run circa 1930 before it was widened and lengthened. Photo: S. E. Douglas. Used with permission.

Donna Buang: the forgotten ski resort

© David Sisson. First published June 2015, expanded and updated to 2023.

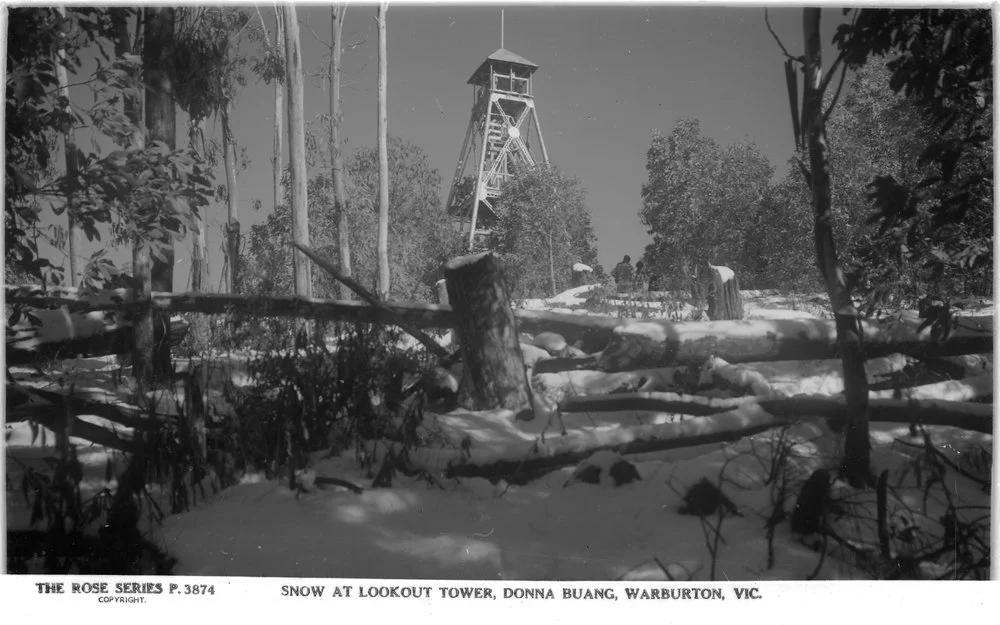

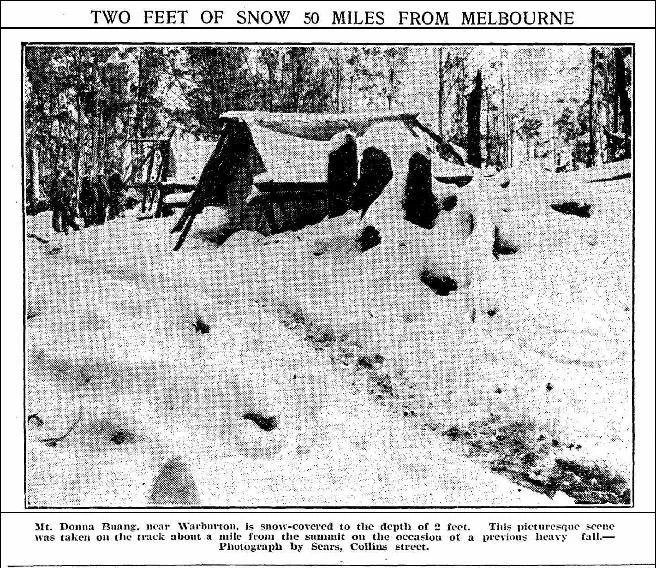

Mt Donna Buang overlooks the town of Warburton in the Yarra Valley. Only 63 kilometres in a direct line from the centre of Melbourne, it was Australia’s busiest ski resort from the late 1920s until 1950. It had ski lodges, cafes, a ski hire, a ski jump and six runs cut through forests of myrtle beech and woollybutt. For over 20 years Donna had thousands of visitors every weekend there was snow.

However, the snow cover was erratic and after the Second World War better transport meant it lost out to resorts with more reliable snow further from Melbourne. Today Mt Donna Buang is a snow play destination with a lookout tower and a couple of nondescript buildings. But a few reminders of its heyday are hidden in the forest among the beech trees.

This is a book length article of over 30,000 words with more than 100 photos and maps. While it's designed to be as phone and tablet friendly as possible, some of the illustrations may not line up correctly in that format, so it's best read on a computer.

Contents.

Click on the main chapter headings to go to that section.

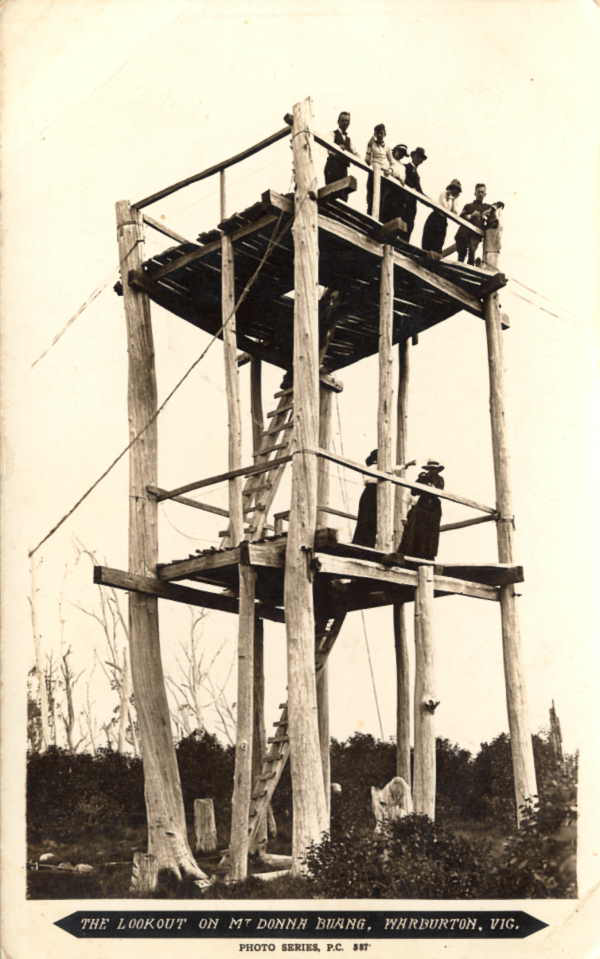

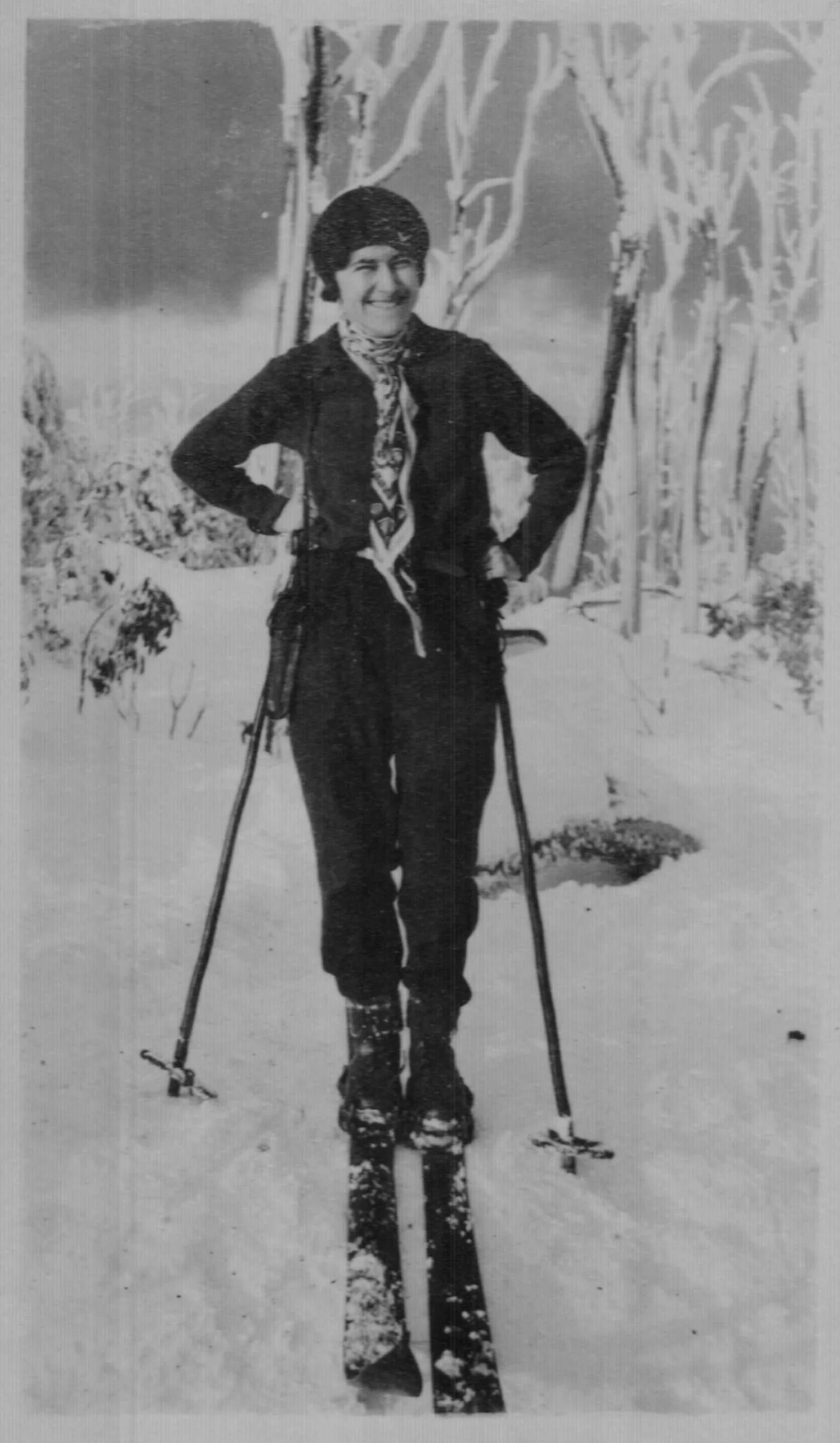

'Nancy' on the summit observation tower, 27 July 1929. Photo by Richard Courtney. Trove record.

1. Background

2. The beginnings of the resort

3. Skiing

- Ski runs

- Crowding

- Volunteer work parties

- Other activities: racing and military training

- A film of skiing on Donna Buang in the 1920s

- Administration and ski politics

- The ski jump

4. Access and transport

- Timber tramways

- The road

- The train

- Buses and service cars

5. Buildings and accommodation

- Accommodation in Warburton

- Club cabins

- Melbourne Walking Club

- University Ski Club

- Ski Club of Victoria

- Rover Scouts

- The summit hut

- Other buildings of the 1930s

- More recent infrastructure

6. Fire, war and the decline of skiing on Donna Buang

- Fire and war

- After the war

Appendices

7. Gazetteer: a directory of Donna Buang names and locations

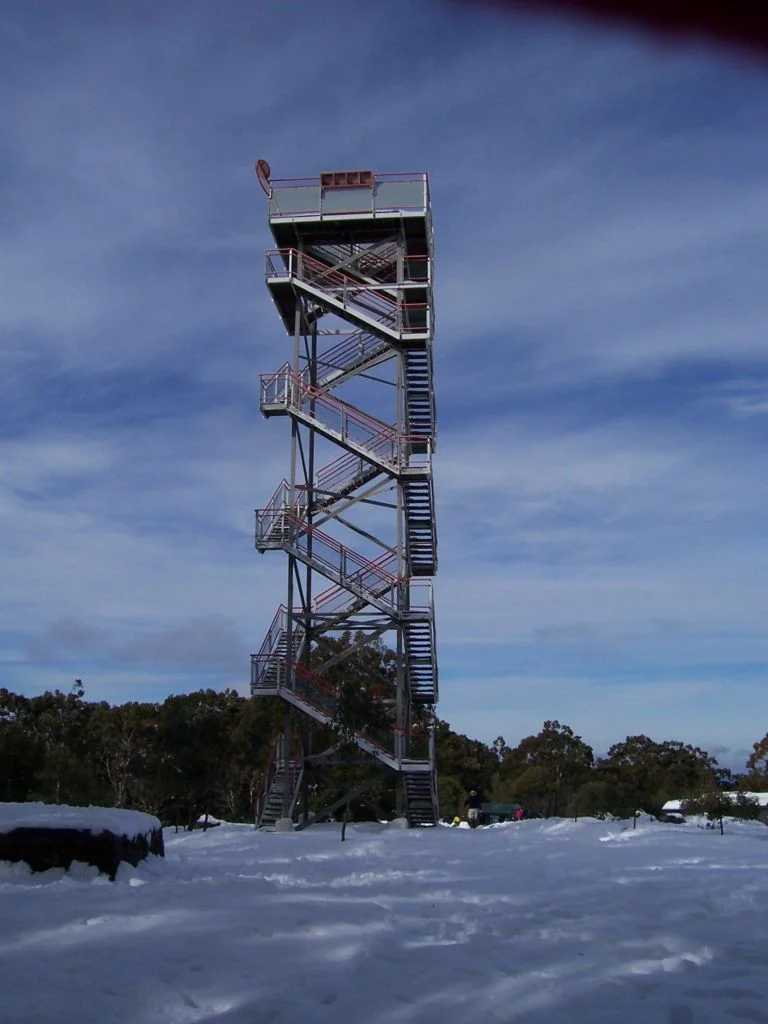

8. Observation towers

9. The warning sign

10. Walks on Mt Donna Buang

- Ten Mile Turntable, summit circuit and Mt Victoria

- Donna Buang via Cement Creek, rainforest and Mt Victoria

- Warburton to Donna Buang via Mt Victoria

11. Historic articles on Donna Buang skiing

- Review of the 1929 ski season. Stan Flattely

- 1930s Donna Buang work party. Mick Hull

- A 1951 semi-obituary for Donna. Ski Horizon

12. Sources and thanks

- Periodicals

- Books

- Web sites

- Thanks

1. Background

There was some recreational skiing at Kiandra in New South Wales in the 1860s and 70s and interest was revived by the construction of the Hotel Kosciusko near Perisher in 1909 and to a lesser extent by the Buffalo Chalet in 1911. However few people in Victoria used skis before the First World War; those who did mostly used them as a practical way of getting around the mountains in winter. Some were miners and from 1886 skiing mailmen traversed the Dargo High Plains between the St Bernard Hospice near Mt Hotham and Grant near the Crooked River goldfields. While a few tourists tried skiing as a novelty, it was never a popular recreation.

This changed in 1919 when the Norwegian born First World War nurse Hilda Samsing took over the lease of the Buffalo Chalet in north eastern Victoria. To boost winter business she imported skis from her homeland and encouraged guests to use them. At the same time, skiing was becoming popular in New South Wales and Tasmania; by the mid 1920s interest in the new sport had achieved critical mass, allowing it to take off. Shops began to stock ski clothing and equipment, ski clubs were founded and accommodation for skiers was built in a variety of locations in the Victorian high country. In 1925 alone, three new ski lodges opened on mountains in the north east of the state.

But these ski lodges in the north east were not convenient for Melbourne based weekend skiers at the time. Why?

Most people worked a 5½ day week with only Saturday afternoon and Sunday off.

Only a minority of families owned a car and many cars of the time were slow and unreliable.

Roads were fairly basic and even some major highways were still surfaced with gravel.

Longer distance travel was usually by train and the railheads nearest to the snowfields, such as Bright, Mansfield and Erica, were distant from Melbourne and on slow branch lines.

It took a lot of time to get to the snowfields at Mt Buffalo and the new 'chalets' at Mt Hotham, Mt Feathertop, Mt St Bernard, Flour Bag Plain and, from 1929, Mt Buller, so they were really only suitable for skiers planning extended trips of at least a week. With an increasing number of skiers living in Melbourne, there was a clear need for a ski destination close to the city, preferably with convenient rail access. Mt Donna Buang was the nearest mountain to Melbourne with reasonable snow cover. It overlooked the bustling timber harvesting and sawmilling town of Warburton, which was only 76 kilometres by rail from the city and 38 kilometres from the terminus of the electrified suburban rail network at Lilydale.

So, when city based skiers began searching for somewhere closer to Melbourne than ski destinations in north eastern Victoria or Gippsland, Donna Buang was exactly what they were looking for. The top car park on the mountain at the Ten Mile Turntable was only 96 kilometres from the city on the roads of the time and those without cars could catch a train to Warburton and either walk or hire a ‘service car’ to take them up the mountain. The only negative was that at 1250 metres, Donna was not high enough to guarantee reliable snow cover through the ski season, although in good years the snow was excellent; 15 consecutive weeks in 1929 and 17 consecutive ‘skiable weekends’ in 1943.

The six Victorian ski lodges in the 1920s.

Extract from the map Broadbent's Central Victoria, 1934.

A 1930s Plymouth car on the road to Donna. Photo USC.

2. The beginnings of the resort

Interest in skiing on Donna Buang began when the president of the Warburton Progress Association took the initiative to invite some skiers to inspect the mountain on 29 June 1924. While their names are unrecorded, they thought the mountain had potential and the Progress Association agreed to clear a ski run, assisted by a £5 donation from the newly formed Ski Club of Victoria. The first people known to have skied on the mountain were a group organised by Stan Flattely on 11 July 1925. It was very much an exploratory trip with the group working out the best route up the mountain, the best method of carrying skis on a pack horse and assessing the best places to ski. They reported that the direct walking track was too steep and slippery to be used regularly, but that the road was quite usable in winter. They also reported that the newly built ski run was far too narrow to be safe.

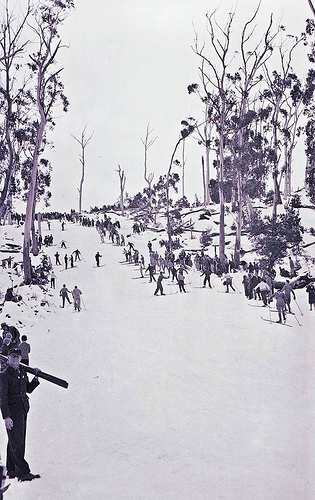

Betty and Peg Nankivell of the University Ski Club at Donna Buang in 1929.

By 1927 skiers had a better idea of the nature of the mountain. A trip report by Jerry Donovan stated ‘...the snow was lightly packed, but after a few runs over the same tracks the pace was much accelerated. The evolutions performed in trying to control speed on a steep slide which owing to fallen timber and tree stumps narrowed to three feet in places, provided comedy for a number of pedestrians who appeared on the scene. Subsequently, when introduced to skis, greater comedy was supplied by the visitors. The germ, was implanted in them, and full information as to “where are skis obtainable?” and “can they be made easily?”... was demanded and supplied before departure. ...

It has been established... that suitable snow does lie on the mountain for many weeks during winter. On the other hand, to get to the snow means an ascent from Warburton of 3,000 feet along either a well graded road (12 miles) or a very steep bridle track (4 miles). Carrying skis up the Short Track is not recommended and the condition of the road is often such that it is impassable to cars beyond Cement Creek... The quantity of fallen timber which is met puts decided limits on the runs which may be had...’

In the next few years, ski runs were cleared and groomed by summer work parties, the road was improved and accommodation for skiers was built on the mountain, so by the 1930s the experience of visitors was much more comfortable.

Local interest in the mountain grew beyond promotion of tourism and the Warburton Ski Club was formed in late 1931, making it the eighth ski club in Victoria.* Warburton locals maintained first aid posts at the Ten Mile Turntable and the summit. Despite the popularity of skiing, there were only two ski lifts in Australia by the end of the 1930s, neither of them at Donna, so skiers on the mountain had to walk back up the side of a ski run and ‘earn their turns’, much like backcountry skiers today. However, the resort had all other facilities that a modern skier would expect to see at a small resort: on-mountain accommodation, day visitor facilities, kiosks selling snacks, first aid posts, a ski hire, shelter huts, a variety of ski runs and a large car park.

* The oldest known ski clubs in Victoria are:

Bright Alpine Club, 1888. (re-invigorated as a ski club circa 1927)

Ski Club of Victoria, 1924. #

Chamois Club of Australia, 1925. (Originally Victorian Alpine Ski Club.) #

Ski Club of East Gippsland, 1926. (Originally Omeo Ski Club). #

Mt Buffalo Alpine Club, 1927 or 1931. (Sources differ on the date, perhaps it began in 1927 and was formally organised in 1931?)

University Ski Club, 1929. #

Wangaratta Ski Club, 1930. #

Warburton Ski Club, late 1931.

# indicates clubs still in existence

Over a dozen more ski clubs were established in the thirties, there were 50 ski clubs in Victoria by the mid 1950s. Other groups such as walking clubs and Rover Scouts were also involved with skiing at the time and many casual skiers were not affiliated with any organisation.

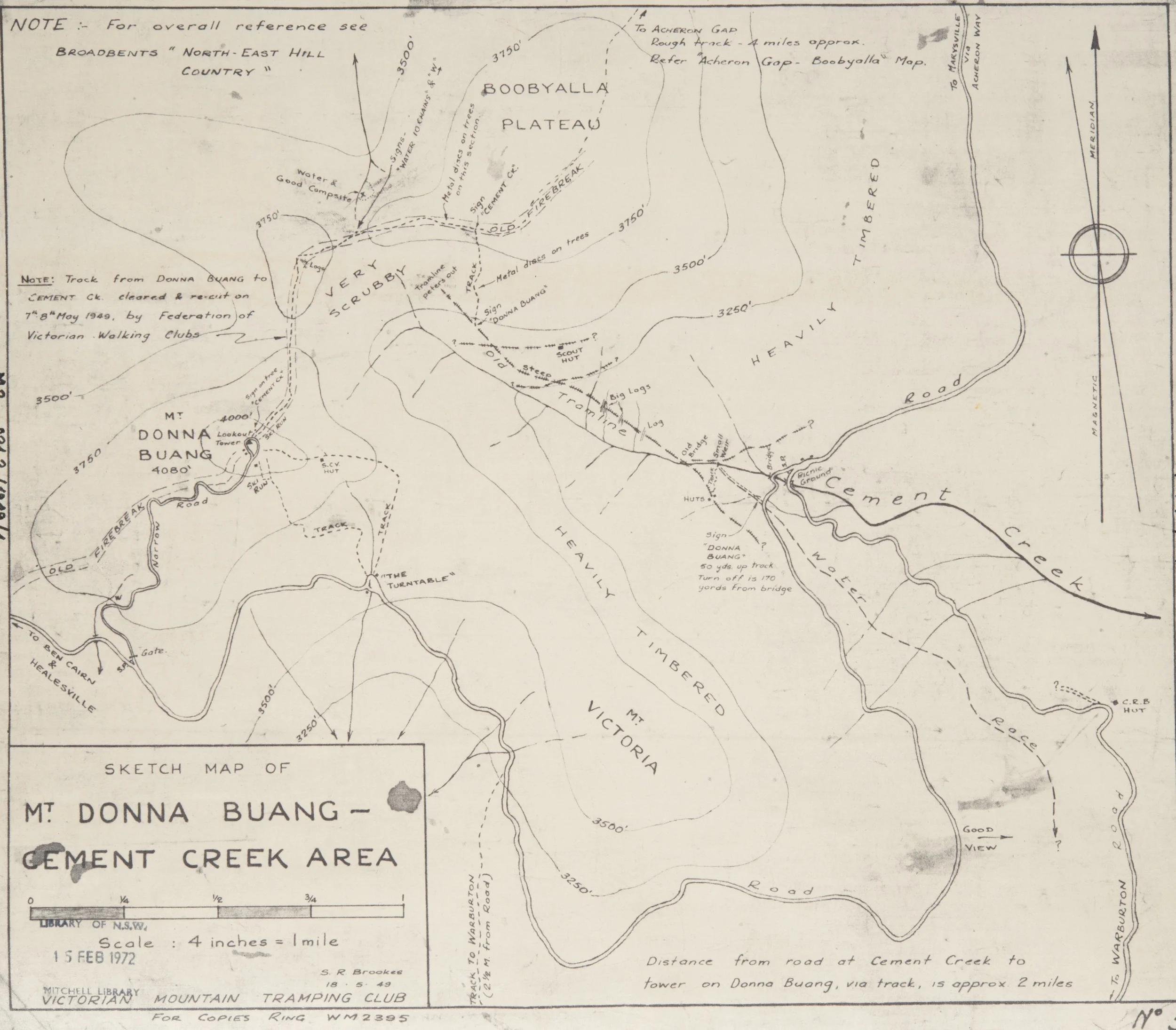

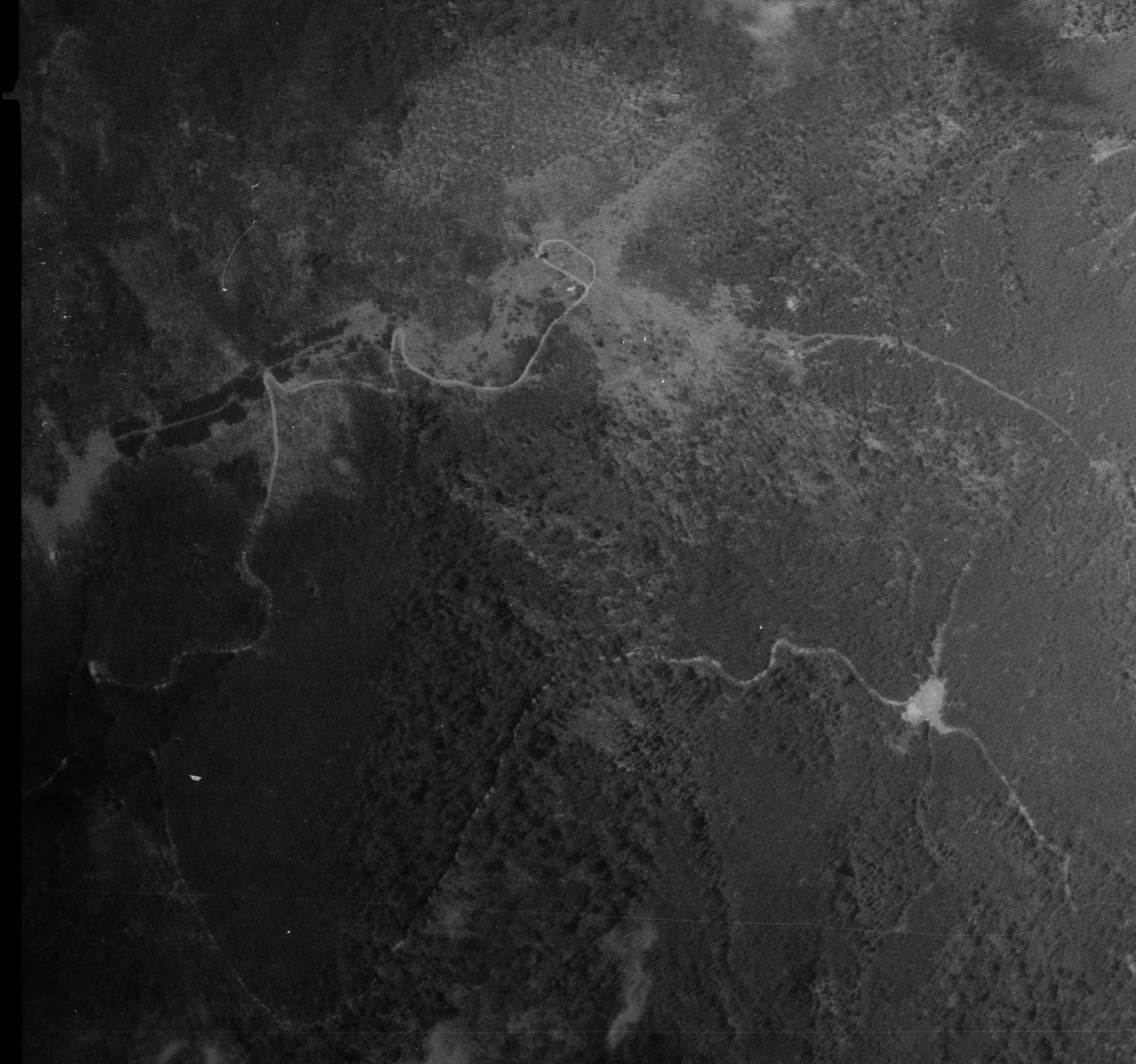

Composite map showing early roads and tracks in bright purple superimposed on a modern map with roads in dull orange and modern walking tracks in grey. The probable locations of six ski runs in 1938 are shown in green. For scale, the grid lines are one kilometre apart.

Looking down the Ski Slide (later widened, extended and renamed the Main Run) in 1929. Photo probably by Monty Kent Hughes.

3. Skiing

Ski runs

The first ski run was built over the summer of 1924 - 1925 by the Warburton Progress Association. Initially it was short and narrow, just 130 metres long and 2½ metres wide, but by 1926 the ‘Ski Slide’ had been widened to 20 metres by the local tourist committee and in February 1929 it was widened to 40 metres. In subsequent years the Slide was renamed the Main Run as more ski runs were cut through the forest. It was further extended and widened in March 1934 and April 1951.

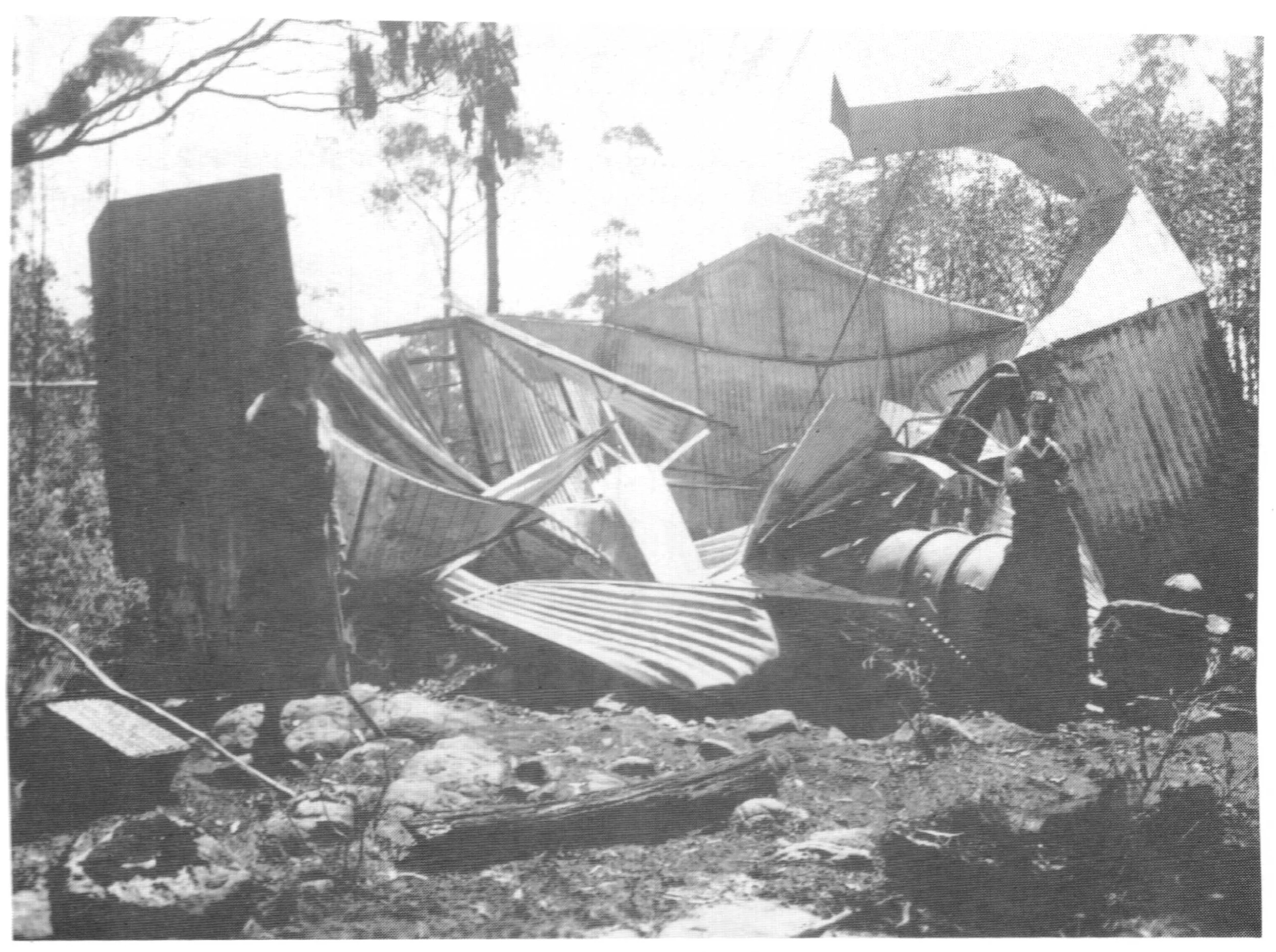

By 1940 the Main Run was unrecognisable after 15 years of widening and lengthening. Photo Mick Hull.

In summer rocks and trees were laboriously dragged clear of the runs, mainly by volunteer work parties. Occasionally they used explosives to remove especially recalcitrant rocks and tree stumps.

The road beyond the car park at the 10 Mile Turntable was closed in winter and skiers accessed the slopes by a direct track from 10 Mile to the base of the Main Run (which is now overgrown). The snow-covered upper section of the road was used as a ski touring route, while a cleared fire break that ran parallel to the top part of the road seems to have been used as a gentle beginners run.

In the summer of 1932 - 1933, another short run was cut to the south of the Main Run. 20 metres wide and 41 long., it was funded by a government grant topped up with £16 from the Ski Club of Victoria, one of the clubs active on the mountain. So by 1934 there were at least two properly built runs, the main one about 130 metres long with a 21 degree slope and the other, shorter and steeper (25 degrees).

Increasing numbers of skiers and the crowding of existing ski runs by sightseers and tobogganists gave an impetus for existing runs to be widened and extended and for more runs to be be built. In April 1936 another new run measuring 270 x 60 metres was cleared to the north east of the summit. This ski run is still followed by the current walking track to Boobyalla Saddle. It appears to have been recommended by the Committee of Management and in part it was a widening of an existing fire break. The work was paid for with a £200 grant from the Public Works Department. In 1937 another £100 was provided to remove remaining rocks and stumps and for slope levelling, what is called 'summer grooming' today.

It is recorded that by 1937, there were six runs on the mountain, but it is not possible to identify them with absolute certainty and their names appear to have been lost. Reconstructing the routes from contemporary writing, a 1944 aerial photo and exploration of the mountain from 2011 to 2014, the most likely locations for the six runs are (clockwise from the north, see the map at the start of this chapter):

A slope heading north east from the summit tower, it was a widened & groomed fire break. The walking track to Boobyalla Saddle still follows it

Probably where the present day walking track descends from the summit area towards 10 Mile. It appears there was a fire break there too.

A slope just to the north of the Main Run.

The Main Run. Starts behind the present day toilet block with a staircase insensitively placed down the middle. (Known as the Ski Slide in the 1920s.)

A slope just to the south of the Main Run. This may have been known as the Jump Run.

The fire break to the south west that ran north east and roughly parallel to the top 800 metres of the original winding summit road.

The old summit road down to the main car park at the 10 Mile Turntable had sharp bends and the gradient was too gentle to be a proper downhill ski run, although it apparently made an excellent cross-country ski touring route. The road was closed in winter and in reasonable snow conditions it could be skied for 3 km, all the way down to the 10 Mile Turntable car park.

Eric Douglas and family taking a break July 1935. The photo gives an idea of ski fashions of the time. The structure in the background is yet to be identified, it may have been a kiosk, a shelter hut, toilets, ski hire or a first aid post. Please send a message if you have any idea.

Except for the moderately graded run along the fire break parallel to the summit road, all these runs were relatively short. Snow cover on the mountain was often marginal and it made little sense to invest energy and money extending ski slopes much below the 1150 metre contour, which is why no cut runs extended down to the main car park at the 10 Mile Turntable which has an altitude of 1050 metres.

Donna is a fair way south of most of today's ski resorts, meaning snow coverage extends to a slightly lower altitude, but while snow regularly falls at 700 metres, at that altitude it generally melts in less than a week or is washed away by rain. So, to maximise the time runs were skiable, work on them was largely confined to the highest parts of the mountain.

The only exception came in the dying days of skiing on Donna Buang when, in early 1951, a work party substantially extended the Main Run utilising £25 funding from the Tourist Resorts fund. The volunteers appear to have been largely locals associated with the semi-defunct Warburton Ski Club and members of the Ski Club of Victoria, one of the clubs with a cabin on the mountain.

To modern eyes, apart from the relatively short length of the ski slopes, the other unusual thing about five of the runs identified is that they are relatively steep. Except for the fire break to the south west of the summit, all would probably be classified as at least 'Blue' (intermediate) at a modern ski resort.

Of course, not all visitors had their own skis or were able to borrow them, so by the 1930s a ski hire service was available. It was run by Erik Johnson Gravbrot who went on to run a horse sled service providing winter access to Mt Hotham in the 1940s before the road to that resort was cleared of snow.

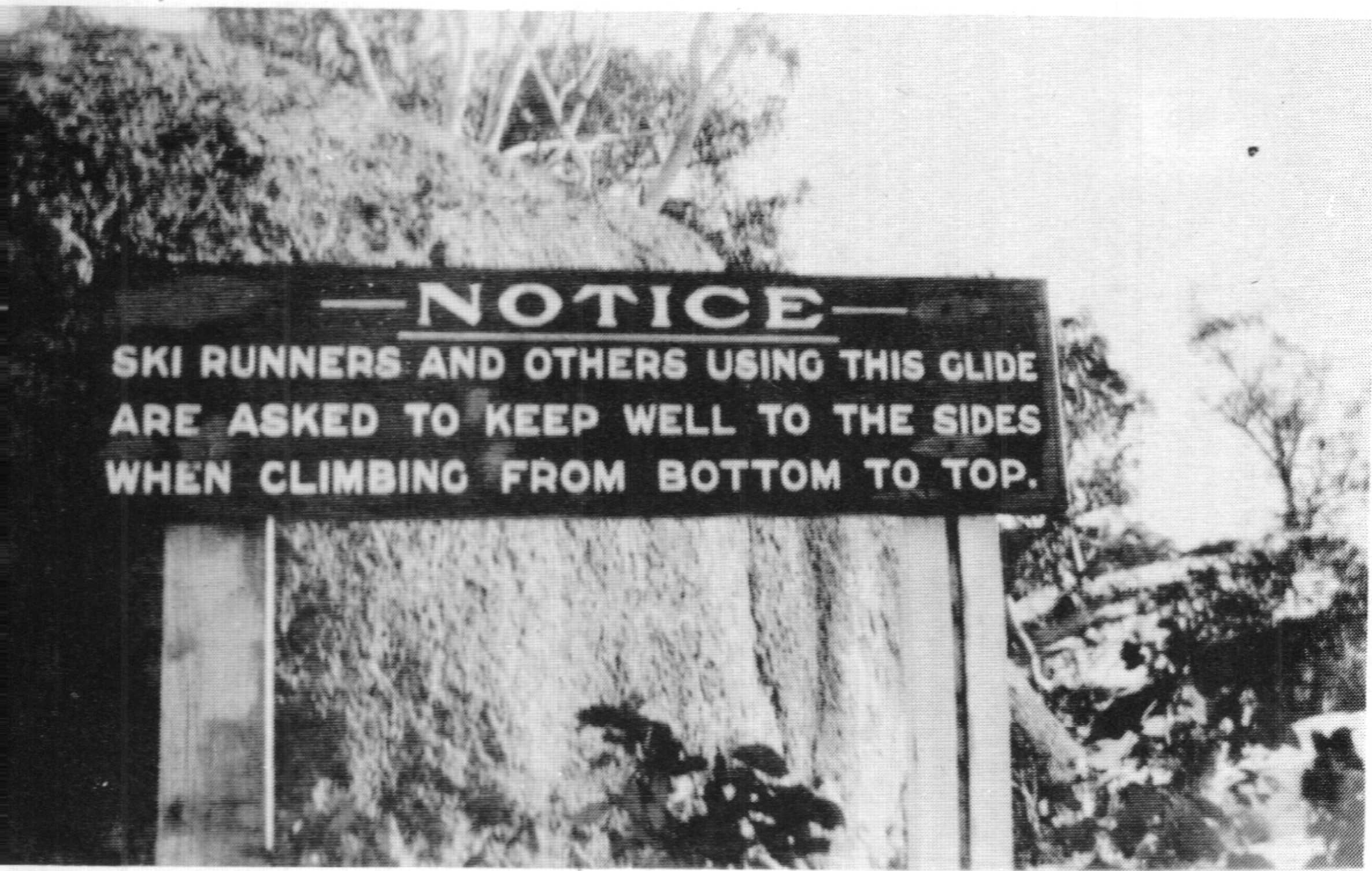

A sign in 1929 urging pedestrians to keep the ski slopes clear.

Crowding

The busiest day at Donna appears to have been Sunday 7 July 1935 when The Argus reported that more than 2,000 vehicles carried 12,000 visitors to the mountain, while another daily newspaper The Herald reported a less precise figure of 'over 10,000'. This is still more than any ski resort in Victoria gets today. How all those people crammed into the relatively small area between 10 Mile and the summit is hard to imagine. Somehow, one of the ski clubs managed to run races on Donna Buang that day.

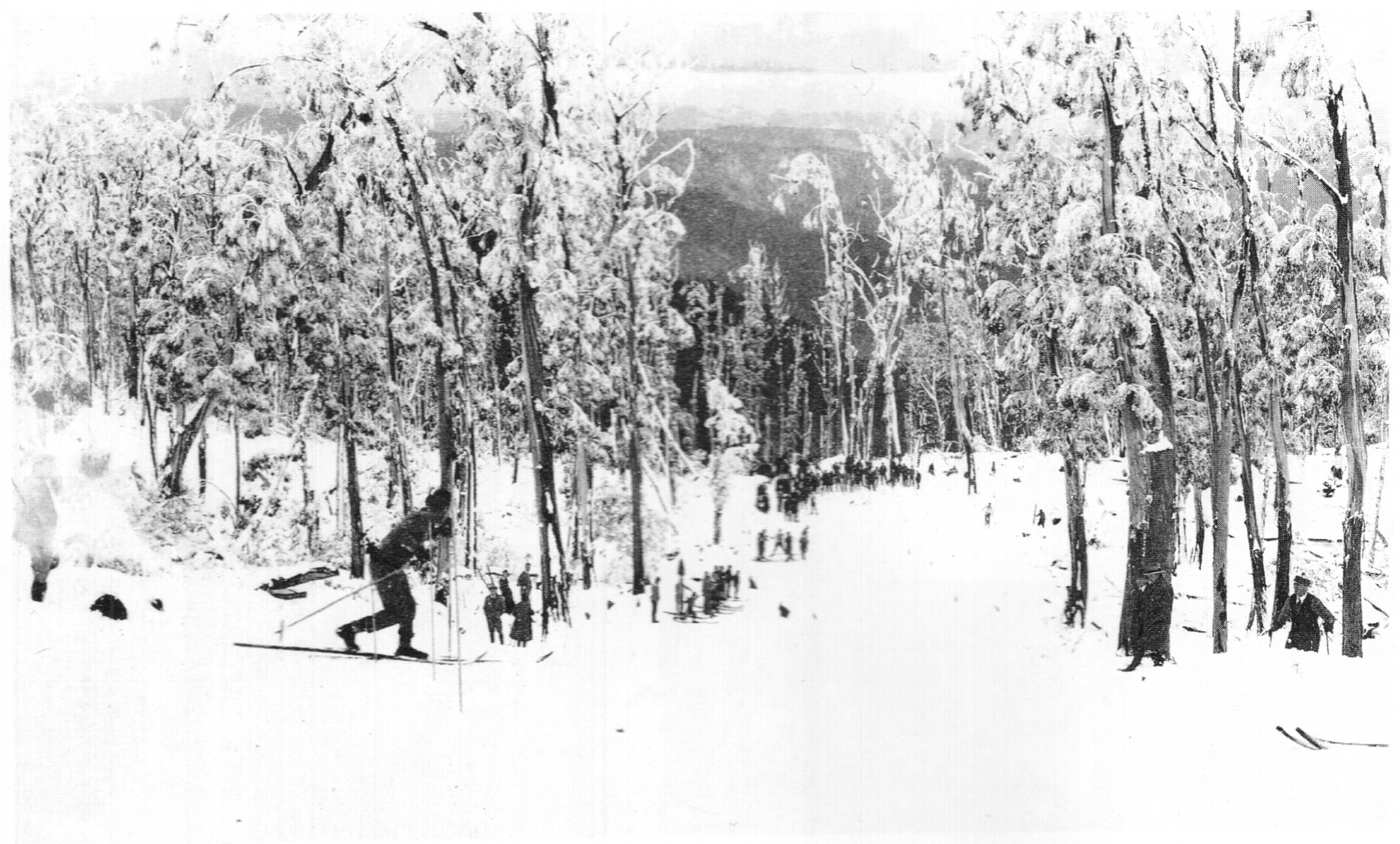

Skiers at the base of the Main Run at Donna Buang. The Argus, 20 June 1932.

While crowds on other days were less extreme, good snow on a weekend always brought thousands of people to Donna Buang. A more typical day was probably Sunday 21 August 1932, when 620 cars visited and there were 2,000 people in the summit area. There don't appear to be formal records of visitor numbers and those quoted are drawn from newspapers and ski magazines. How accurate they are is open to question; on one day in August 1934 there must have been an awful lot of vehicles shuttling up and down the road for 'over 100 cars and vans' to deliver 'over 5,000 people' to the mountain. But whatever the precise figures really were, there is no doubt that Mt Donna Buang was a very crowded place whenever there was decent snow in the 1930s.

Fortunately for the skiers, most people simply came to visit the snow rather than to ski. However on busy weekends, crowds spilled onto the ski runs making skiing difficult and conditions dangerous for both sightseers and skiers. In 1933 a fence was built to keep non skiers off the slopes, but even after the fence was extended in the summer of 1935 - 1936, it was still not effective as the penned in non skiers simply climbed over the fences. Another attempt to deal with the problem was to build a toboggan run to give the snow players somewhere away from the ski runs to try out their mostly rented equipment.

But crowding of these areas often made it impossible to keep snow players and tobogganists off the ski slopes. There just wasn't the space for thousands of people to enjoy themselves in the treeless and cleared areas of this relatively small mountain and the crowding was hardly conducive to an enjoyable ski trip with a group of friends.

As the popularity of Donna Buang grew, so did the level of frustration by skiers. As early as 1928 Eric Stewart of the Melbourne Walking Club reported that ‘several parties of visitors arrived to see the snow, and in the nature of their kind, engaged in snow-balling (which we did not mind) and selected... our narrow ironed [ski] track to wallow through (which we did mind). Some of my remarks were, I fear, more pointed than polite.’

Non skiing 'visitors' walking on a ski run. Source: NLA

The crowding caused increasing concern amongst some skiers and irritation amongst others. In 1933 The Sun newspaper sensationally reported that 'war' had erupted between skiers and tobogganists and that a skier used an axe to destroy a toboggan that had been used on a designated ski run. The problem was slightly eased when the Main Run was widened in March 1934 and a new track for pedestrians was cut parallel to it.

One of the more intense written responses from skiers was a mid 1930's letter to the monthly ski magazine Schuss by Sandy McNabb. “... the congestion which has followed from wide publicity and the lack of facilities for casual visitors have caused misgivings to [skiers] who naturally wish to make the most of the limited ski runs... the suggestion of opening the road right to the summit must call a strong protest from skiers, Imagine the results with only 500 cars parked near the top and several thousand people dumped there. With all the cleared space occupied by cars there would be only one place for them to overflow and that would be on the ski runs... and the road would be completely lost to skiing... a snow plough would be necessary to keep it open and heavy maintenance charges would be involved. ... [Instead] let all the money available be spent on developing runs, trails and other accommodation... Cars are only required to get to the snow and not through it.”

Clearly McNabb believed in segregating skiers and those he described as merely ‘visitors’ as much as possible, presumably by encouraging them to stay down at the 10 Mile Turntable, away from the ski slopes and the observation tower on the summit. But his sentiments were shared by less blunt skiers and their lobbying ensured the road to the summit beyond 10 Mile remained closed in winter.

The Herald newspaper reported that 'over 10,000 persons' visited the mountain on the first Sunday in July 1935 and 'their transport presented a traffic problem of such magnitude that conferences are being held to determine how best such a concentration of vehicles can be handled in the future'. Arthur Shands, the president of the Ski Club of Victoria responded by proposing that a resort entry fee should be charged. This would reduce visitor numbers as well as funding further improvements to the mountain for skiers. The idea was strongly opposed by A. D. Mackenzie, chief engineer of the Public Works Department who had supervised the rebuilding of the road two years earlier. He argued that access to the mountain should be free and open to all.

This overcrowding by sightseers and tobogganists as well as skiers was the prime impetus for more ski runs to be built. As well relieving the crush, they also provided a greater variety of slopes for skiers, who in the early 1930s had been restricted to only a couple of properly built runs. However even with expanded skiing and snow play areas, the problem was not resolved and as late as 1947 a ski club newsletter reported 'Unfortunately snowballers and traffic jams were as bad as in the bad old days, mostly due to lack of suitable control'.

A volunteer 'working bee' on Donna Buang. Schuss, June 1945. p. 115.

Volunteer work parties

With skiing on the mountain becoming increasingly popular, it was only a matter of time before locals became interested and the Warburton Ski Club was founded in 1931.

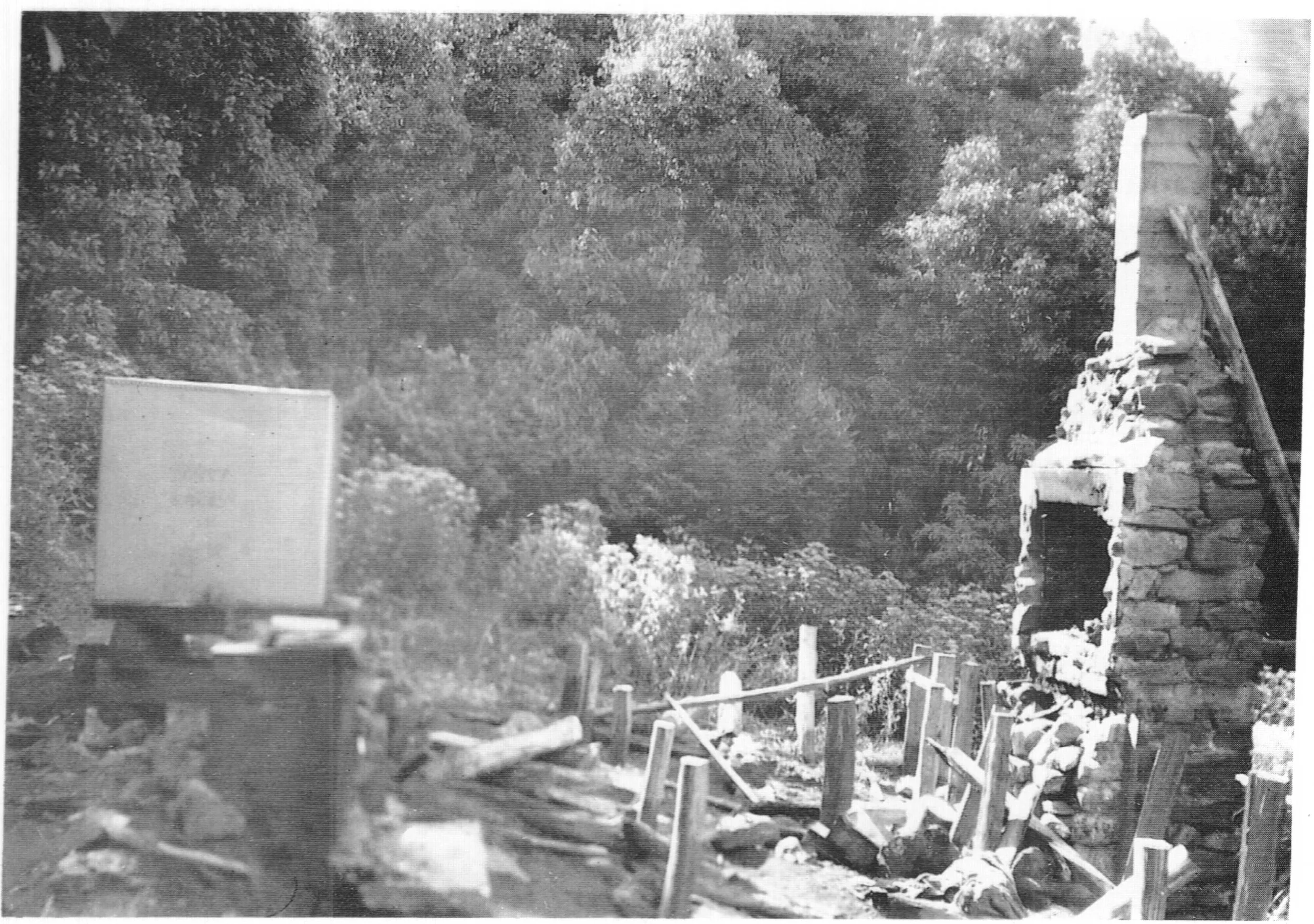

Post logging debris and regrowing woollybutt below the lookout tower. This photo gives an idea of the work involved in clearing the ski runs.

Much of the hard work of improving the ski runs and fencing them off from areas frequented by Sandy McNabb's dreaded 'visitors' was undertaken by locals from the Warburton Ski Club, as well as members of the four clubs with accommodation on the mountain, although it is likely that other skiers and clubs assisted as well. The workers were volunteers and most of the funds needed were donated by the clubs and local tourist businesses, although occasionally grants were obtained from government agencies to cover the cost of materials and specialist labour.

Donna had its heyday in the late 1930s. The mountain was popular, clubs had built accommodation on the mountain and new ski runs were cut through the forest of woollybutt and myrtle beech. But the January 1939 wildfires, followed seven months later by the outbreak of the Second World War slowed things down. Wartime petrol rationing and many of the most active skiers enlisting in the armed forces reduced both the number of skiers and the ability to do summer maintenance work. When the war finished, after a brief revival, skier's attention rapidly moved to other resorts, initially Hotham and Buller but a few years later Falls Creek and Baw Baw as well.

By 1950 ski visitor numbers were in steep decline, the University Ski Club had transported their lodge to Mt Buller and the end looked near. But at least one club remained optimistic about Donna Buang's future. The Ski Club of Victoria organised volunteer work parties in March and May 1951. Ski runs were cleared of fallen timber, the old wooden jump was rebuilt in stone and the Main Run was extended. The Public Works Department contributed £25 to cover costs. Walk magazine reported 'visitors to the mountain during April and May were interested in the explosive efforts of Ski Club members improving the ski jump and run-out in preparation for the coming winter. Much gelignite was expended in removing large boulders from the track'.

It appears the final work parties on the ski runs were comprised of locals from the upper Yarra area and were organised by Mick Smith. Over summer Sundays in 1951 - 1952 they extended the Jump Run and linked it to the base of the Main Run by a curved route through the trees. But by the 1952 ski season there were very few skiers left to enjoy these improvements.

A modern staircase has been built down the middle of The Main Run, thwarting any potential skiers who may wish to recreate the experience of 90 years ago. © David Sisson.

Other activities

In the 1932 season there was skiable snow on 56 days including 12 Sundays. On Sunday 21 August, 620 cars visited and there were 2000 people in the summit area. That appears to be a fairly typical number for Sundays of that year.

Racing

In the 1930s skiing had not quite split into separate downhill and cross country disciplines, so while the main focus on the mountain was downhill skiing, cross country was also popular in the less steep areas. The Herald reported that a 'Langlauf' race held on 11 July 1935 in 'slow conditions' along the snow covered road from the summit to the 10 Mile Turntable was won by T. Fisher in 14 minutes 15 seconds. (The route was along the original summit road and not the shorter and steeper road built in the 1970s.)

The University Ski Club has records of downhill racing on the mountain and the Ski Club of Victoria held downhill and cross country races on Sunday afternoons from the late 1930s until at least 1951. It is possible that other clubs raced on Donna Buang as well.

Australian ski troops on patrol in Lebanon, 1941. Australian War Memorial.

Military training

In 1935 the Brighton Rifles, a unit of what is now called the Army Reserve, conducted 'snow manoeuvres' on Donna Buang. This may not have been as frivolous as it sounds as a few years later the Australian Army found a use for experienced skiers in two rather different theatres of war.

In 1941 the 1st Australian Corps, Ski School was established at The Cedars near Bsharri in the Taurus Mountains of Lebanon. Initially it was planned for Australia’s first ski troops to fight the Vichy French in the Syrian Campaign of the Second World War. This was part of a larger project with the intention of training mountain troops to operate on skis in winter and in difficult terrain in summer. It was planned to have two companies of about 200 of these specialist mountain troops in each of the three Australian divisions deployed to the Middle East at the time, but only the 9th Australian Division Ski Company was formally established..

However the French were defeated before the courses began, but it was decided to go ahead with the training anyway as trained mountain troops had the potential to be useful throughout Europe. However with the entry of Japan into the war, the 6th, 7th and 9th divisions were gradually reassigned to tropical areas, so their ski training was never utilised. The unit trained over 200 soldiers in ski warfare before it was disbanded in late February 1942. The work in establishing the ski school and developing courses was not wasted as the facilities at The Cedars and nearby areas were taken over by the British. In 1942 it became the (British) IX Army Ski School, then the Middle East Ski School in 1942-1943 when it was expanded to cover all aspects of mountain warfare, including both skiing and rock climbing before its closure in 1944.

In 1943 prisoners of war on the equator in Singapore established the Changi AIF Ski Club as a way to occupy themselves. The club’s weekly lectures and discussions proved to be quite a morale booster in the difficult conditions of the Changi prisoner of war camp. The president was Captain Tom Mitchell, the four time Australian combined ski champion who had funded the construction of the Donna Buang ski jump. It was probably the only ski club in history where none of the members saw snow during the existence of the club.

Hat badge of the Brighton Rifles

While it is not known if the skiing members of the Brighton Rifles in 1935 later found themselves training to fight the French on skis in Lebanon or if any were imprisoned by the Japanese in Changi, the army reserve exercises on Mount Donna Buang may actually have been quite useful.

As to the Brighton Rifles themselves, the unit was established in 1921 as the 46th Infantry Battalion, but when war broke out in 1939, many members of reserve or ‘militia’ units joined the regular army and were deployed overseas. When there was a danger of Japanese invasion, those who had remained with the unit were sent to Queensland where, as part of the 3rd Division, they trained in jungle warfare. It was amalgamated with another battalion in late 1942 and in 1943 was sent to fight at Milne Bay in New Guinea as part of the 5th Division.

Note 1: The army also used the area above the tree line on Mt Buller in summer during the war as training in the use of Universal Carriers (aka Bren Gun Carriers) a type of light armourned vehicle, in mountain environments. (Summers p. 9)

Note 2: I’ve been corresponding with a couple of people about the 1st Australian Corps Ski School and it would make an excellent subject for a book, article or YouTube video. However I’m not sufficiently versed in military history and none of us have the time to write about it at length or produce a video. However I have a long list of printed, photographic, online and video resources as well as useful contacts for anyone who may be thinking of doing some work on the subject. Please contact me if you’re interested.

A film of skiing on Donna Buang in the 1920s

A typical home movie, the film shows the basic conditions on the mountain before the cleared runs and vastly improved facilities of the 1930s. Starting in 1926, just a year after skiers first ventured onto Donna, it doesn't feature overly stylish skiing. Later there is a short interlude at Mt Hotham featuring Helmut Kofler, which dates that part as 1928, as Kofler only spent one year at Hotham before moving to Mt Buller where he was the manager of the Chalet on that mountain until his death a decade later.

The section from 1.24 to 2.20 conveys what the 1920s experience was like for ordinary skiers on Donna Buang. The packed car park gives an idea of how crowded the mountain was just a few years after it was discovered by skiers and other snow tourists. Unfortunately who made the film it is unknown.

Administration and ski politics

Oversight

From 1919 to 1983, Crown land in Victoria that had been used for purposes such as mining or farming was generally managed by the Department of Crown Lands and Survey (usually known as the Lands Department), while Crown land that had never been occupied for long term use and which was not intended to be sold, was mostly under the control of the Forests Commission. The Forests Commission was run by foresters and was mainly concerned with sustainable timber harvesting and general environmental management including preserving areas of special scenic or ecological value. Needless to say, tourism was not a field within most foresters range of expertise. However, in 1924, in recognition of Donna Buang's scenic attraction, timber harvesting was prohibited within 101 metres of the Donna Buang road. The logging contractors, T. J. Currie and Co, claimed this set them back a huge £9,000 through loss of timber and additional earthworks necessary for their tramway to cross the road.

While the Forests Commission was expert in the allocation and supervision of logging coupes, they soon found themselves with different responsibilities on the mountain when it became evident that Donna Buang was more than a just a minor scenic destination and they were in control of an increasingly busy tourist resort. So in 1933 a committee of management was established to facilitate communication between city bureaucrats, local Forests Commission officials (based nearby at Powelltown), the tourist industry in the area and representatives of skiers. Members of this committee had views that occasionally clashed, but overall the Committee of Management helped smooth communication and decision making between parties with interests on Donna Buang.

The SCV versus almost everyone

However ski politics did cause some tension on the mountain. Beginning in the mid 1930s, through to the mid 1950s, the Ski Club of Victoria attempted to assert itself as the controlling body of skiing in Victoria. Not surprisingly this didn't go down too well with the 20 other ski clubs that existed in the 1930s, or with private skiers with no club affiliation. Despite suggestions from as early as 1932 that a state wide 'Ski Council' be established, tensions were mostly controlled before the Second World War and suspended during the war,. But by 1945 ski clubs were tired of attacks on them by the SCV and their attempts to levy fees on users of ski huts which the SCV did not own such as Cope Hut on the Bogong High Plains.

Things culminated in 1947 when most of the other clubs formed the Federation of Victorian Ski Clubs as a peak body for Victorian skiers and invited the SCV to join. The SCV responded by printing an eleven page declaration of war in their club magazine and subsequent correspondence from both groups is full of 'colourful' language, although the Federation were careful to be strictly non-partisan in all their publications including the monthly magazine Ski Horizon. In the early 1950s the FOVSC established an “Olive Branch Committee“ to reduce tensions and reconcile the SCV with the majority of skiers in the state. Eventually, in 1955, the heavily outnumbered SCV was persuaded to back down from its demands that other clubs pay an affiliation fee if they wanted input into the club claiming to be the administrative body of skiing in Victoria. From 1955 a unified organisation, the Victorian Ski Association represented all skiers.

The Ski Club of Victoria still exists and it has a lodge at Mt Buller, but it long ago abandoned any delusions that other clubs should pay homage to it. This dispute deserves an article of it's own, but it's sufficient to say that there were no serious inter club tensions in New South Wales or Tasmania. In those states, ski clubs seemed to be able to co-operate to further the interests of all skiers.

THE SCV's campaign against the new ski run printed in The Argus. 4 April 1936. Note the SCV's provocative claims that they were "the" Ski Club and that the Main Run was their run, despite funds for it being contributed by government agencies and local businesses while labour to improve it also came from several other ski clubs.

One of the opening shots of the SCV's declaration of hostilities was fired on Donna Buang in early 1936. To alleviate overcrowding, the Committee of Management approved the construction of a new ski run on the north east slopes, some distance from the existing runs which were to the east and south of the summit. This appears to have been a good location as the slope still holds good snow and it incorporated a cleared fire break which would have reduced the cost of building it.

In one of the first instances of the SCV "not playing well with other children", the club appears to have resented that others were involved in deciding where the new run should be and it began a campaign to depict the new run as both a waste of money and subject to such strong sun that snow that fell on it would quickly melt.

However after it was built, the new run proved to be fairly popular with skiers and while it is now slightly overgrown, it still holds good snow whenever it falls.

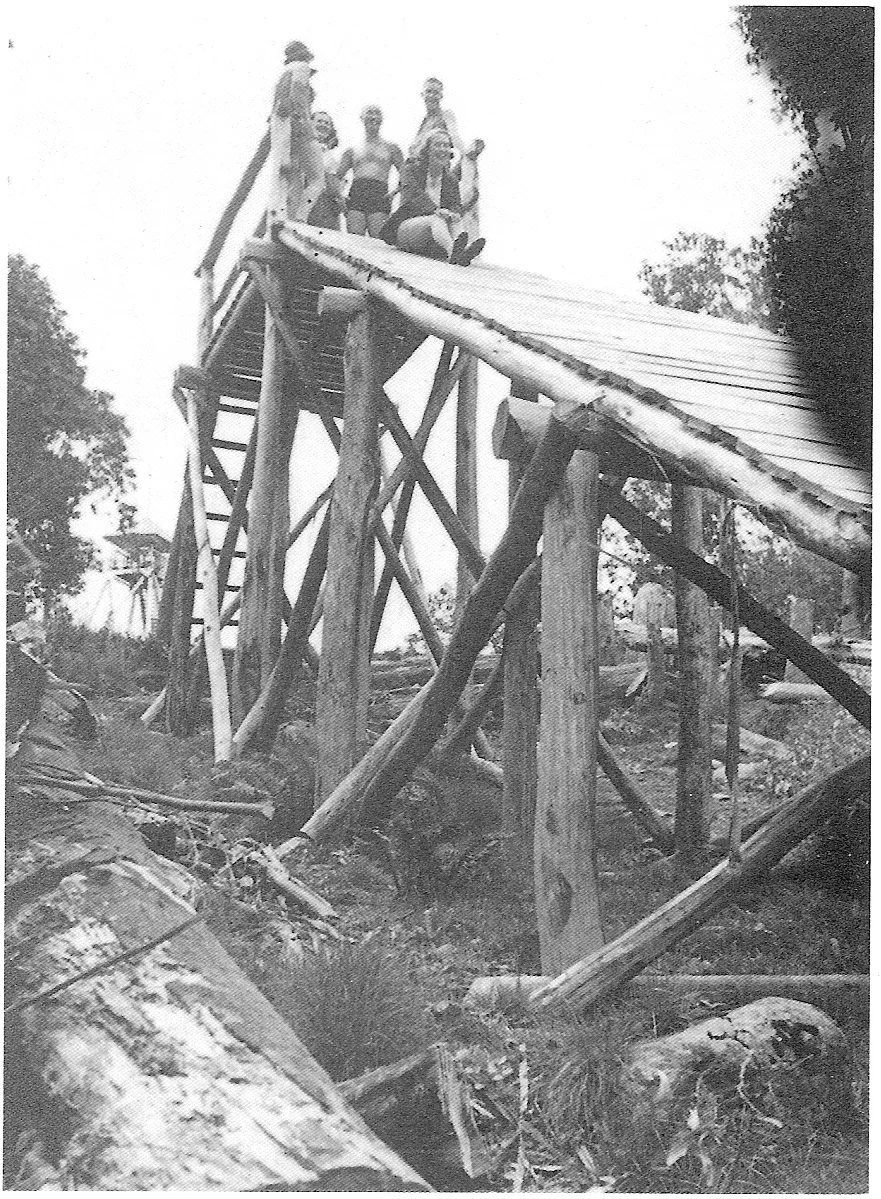

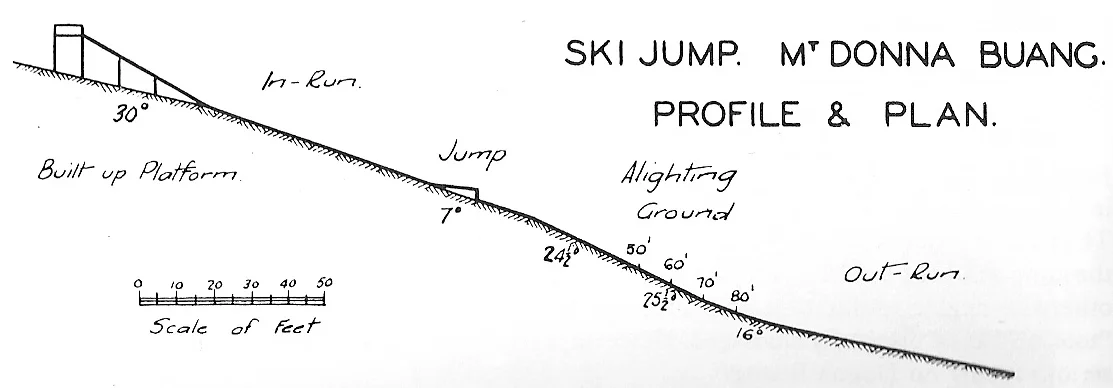

The original wooden platform at the top of jump slope in summer. The summit tower can be seen behind it to the left. Photo Mick Hull.

The ski jump

Ski jumping played a part in Victorian skiing from the 1930s to the 1960s. However this was the old nordic sport of distance jumping rather than the aerials at which Australians have excelled in recent decades. Jumps were constructed in many ski areas from the early 1930s culminating in 1966 with the enormous Ross Milne Memorial Jump near the top of the Gully Chairlift at Falls Creek. However despite good facilities and promotion, mostly by migrants from Europe, jumping never really ‘took off’ in a big way with Australian born skiers.

The wooden take off platform on the jump at Donna Buang. Photo USC website.

In 1932 a ski jump was built at Donna Buang by members of the University Ski Club. Clearing of the jump slope was funded with a generous £25 donation from Tom Mitchell. (Mitchell was Australian combined ski champion for four years and went on to assist and promote ski related causes as a member of state parliament from 1947 to 1976.)

The jump was designed by Norwegian born Martin Romuld who was the state ski jumping champion for much of the 1930s. Romuld worked as an engineer on the Kiewa hydro electric scheme and lived in a cottage on the Bogong High Plains all year round. As his home was in the snow for four or five months each winter, he had plenty of opportunity to practice.

Romuld designed the Donna Buang jump to minimise construction work. At the top, a three metre high wooden platform led to the natural slope of the hill. A small platform was built further down the jump slope at the take off point. The whole length of the jump slope was about 32 metres. In 1933, Romuld jumped 18.3 metres. The best an Australian could manage was 15 metres jumped by George Hulme in 1935.

However despite the attempts of Scandinavians such as Romuld and Eric Johnson Gravbrot, the owner of the Donna Buang ski hire, plus a few central European skiers, jumping never became terribly popular with local skiers and the jump may not have been used all that much. But some Australians did take up jumping; Tom Fisher and Derrick Stogdale actively promoted the activity on Donna Buang to members of the Ski Club of Victoria in the late 1930s.

It appears the jump survived the 1939 fires, although it may have become derelict during the six years of the Second World War when there would not have been the resources to maintain it. Reputedly it eventually fell down. In March 1951, when the mountain was in steep decline as a ski destination, former members of the defunct Warburton Ski Club assisted by members of the Ski Club of Victoria, renovated the jump area and trucked in 30 tons of stone which was used to rebuild the take off platform at the edge of the then road. The group also cleared rocks and scrub from the runs and extended the length of the nearby Main Run. The cost of all this work was £45/16/6, the State Development Committee contributed £25, the remainder being covered by the SCV.

Despite the obvious decline in Donna Buang’s popularity amongst skiers, some remained optimistic about its future and in the summer of 1951 - 1952 Mick Smith organised a group of locals to extend the jump run, including linking it to the Main Run by a route curving through the trees. Work parties were run on a number of Sundays with stumps being blasted and logs cut to provide a good clear extension to the run.

But by that time, keen skiers had already moved to higher mountains to the north and east, so there were not many left at Donna to benefit from the new work and the jump was hardly used after the 1952 ski season.

In the mid 1970s the stone ski jump was bulldozed by the Country Roads Board when, despite protests from locals, 400 metres of the road near the summit was realigned. Some of the rubble from the stone jump can be seen above the modern road, 100 metres south east of the summit area shelter hut.

1925 map of Warburton and district. From Tourist guide to Warburton and district.

The Knob engine house and the haulage leading up to The Pimple. Three seperate inclines lowered timber from Mt Victoria down to Warburton and hauled the bogies back up. Rose postcard.

4. Access and transport

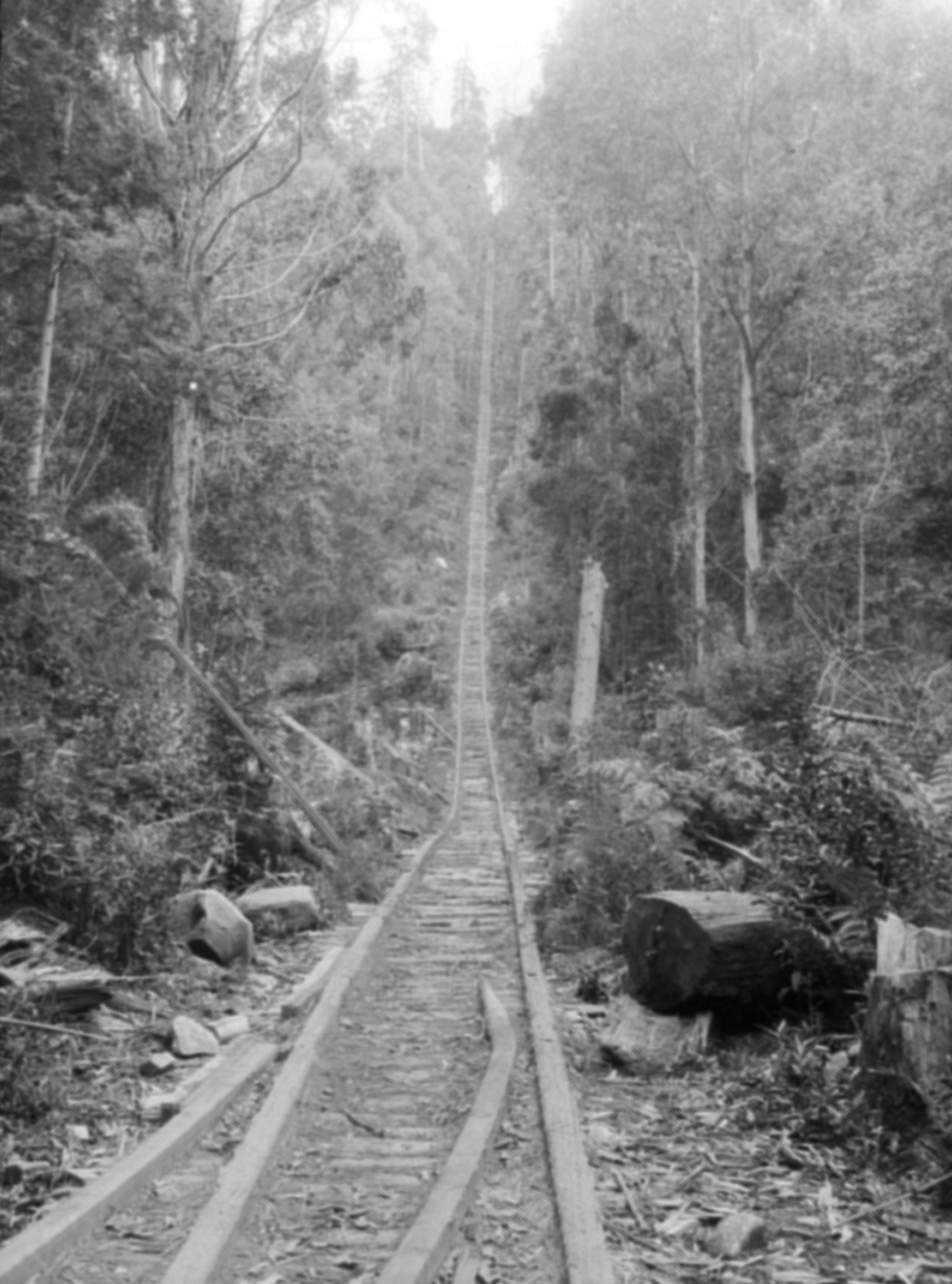

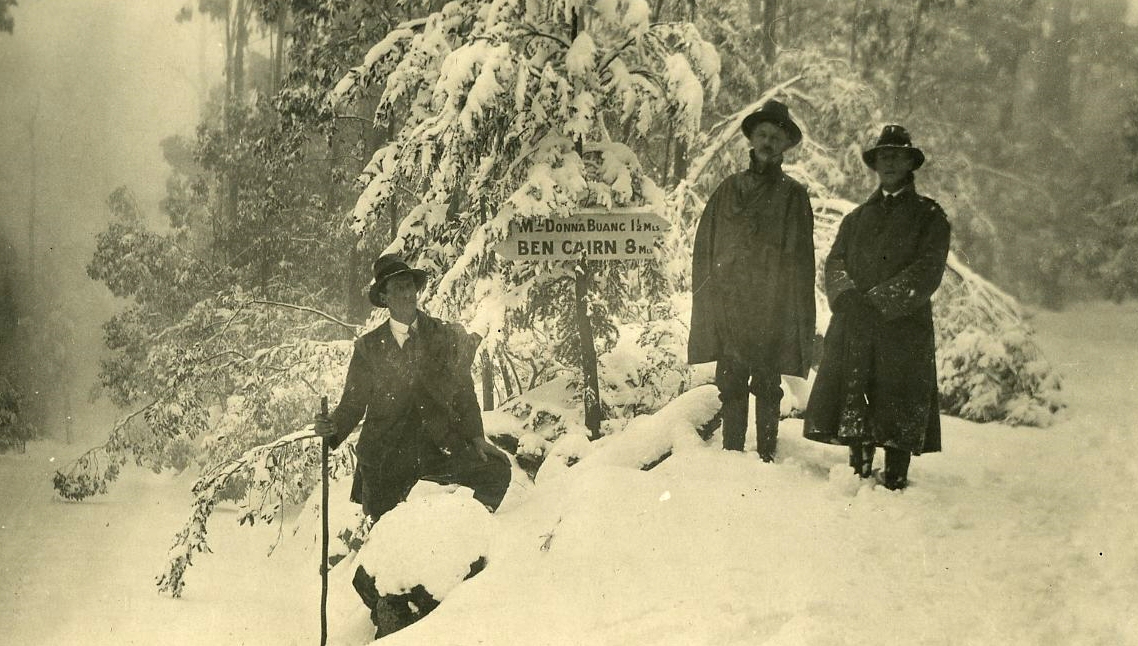

Jacob's Ladder incline on Currie's tramway from Millgrove, terminated at the Ben Cairn Road, 2 km west of the turnoff to Donna Buang Summit. It continued to be used for pedestrian access to the mountain long after the tramway closed in 1934.

Background. Most mountains and ski hills in Victoria were initially accessed and opened up by miners and mountain cattlemen, but unlike some other hills nearby, Donna Buang had no minerals and the grazing potential was very modest; lying below the treeline in an area of tall ash forests and temperate rainforest, there were no natural snowgrass plains and very little grass on the forest floor. As its slopes were too steep for farming, the mountain was largely untouched and, until the start of the 20th century, it received few visitors apart from the occasional surveyor or unsuccessful gold prospector.

Timber tramways

Plans to build a railway to Warburton were initially thwarted by the 1890s economic depression, but when the railway finally arrived in 1901, it massively reduced the cost of transport and large scale timber harvesting became viable. Before the railway arrived, farmers who cleared land often had no alternative but to burn the timber. However by the turn of the 20th century Melbourne was recovering from the depression of the 1890s and the forests of the Upper Yarra valley were soon being harvested to build new housing. Within a few years, eight cable haulages and funicular tramlines connected sawmills in the Yarra valley to the top of the Ben Cairn – Donna Buang ridge. At the top of these haulages, several timber tramways extended to within a few hundred metres of the summit.*

The timber tram on the ridge between Mt Victoria and Donna Buang ceased operating when useful timber was cut out in 1921 and the tramway accessing upper Cement Creek on the northern slopes closed in 1923 or 1924. To the west, timber harvesting lasted a little longer and the notoriously steep Jacobs Ladder incline on Currie's tramway from Millgrove was a popular access route for members of the Melbourne Walking Club.

While the timber harvesters had mainly moved on by the time skiers arrived on Donna Buang, the routes their tramways followed remained useful as access tracks for years afterwards. Material salvaged from buildings abandoned by the logging industry was later utilised by the Rover Scouts and University Ski Club in their own structures on the mountain.

* The story of timber harvesting on Mt Donna Buang is covered in comprehensive detail in chapters 3, 4 and 6 of Mike McCarthy’s excellent book. Mountains of ash: a history of sawmills and tramways of Warburton and district. Light Railway Research Society of Australia, 2001. It has detailed and accurate maps of the many former tramways on Donna Buang.

Map of early 20th century timber tram lines and haulages on the southern slopes of Donna Buang. Timber mills are indicated by a red triangle, the tram lines are shown as grey lines. The northern slopes were not logged as they were in the closed catchment of the Watts River which was used to supply water to Melbourne. Extract from a much larger map based on Mike McCarthy,s work on the Victoria’s Forestry Heritage website.

The Donna Buang Road at 8 mile in 1925. From Tourist guide to Warburton and district.

The Road

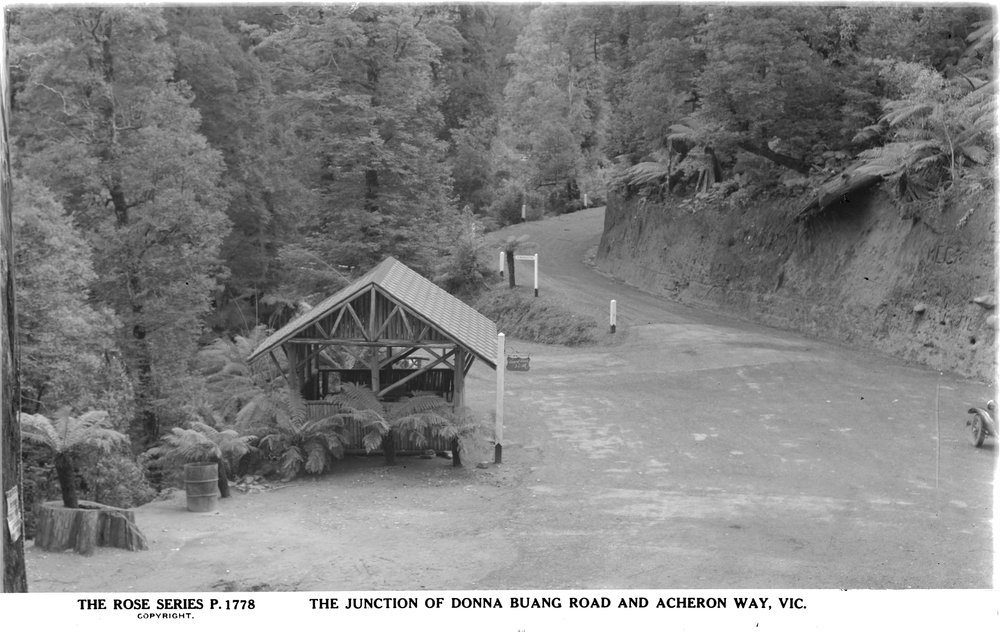

The unsealed, single lane, Donna Buang road. State Library of Victoria.

A steep foot track had been built from Warburton to the summit of Mt Donna Buang by sustenance workers in the 1890s depression (probably today’s Martyr Road to Mt Victoria walking track) and it was kept in good condition. In 1911 Carlo Catani, Chief Engineer of the Public Works Department, fresh from developing Mt Buffalo by improving the road, building the Chalet and the lake that was named after him, visited Donna Buang. Catani was sufficiently impressed with the mountains tourist potential that a moderately graded access route to the mountain was quickly surveyed. Initially a 15 km bridle track was built at a cost of £400 and opened on 2 April 1912. It was upgraded to a 4½ metre wide road in the early 1920s and by 1925 it was being described as a ‘well made road’.

By the 1930s many skiers had access to a car and would drive up the mountain to the snowline before walking to the ski runs or, if they were staying overnight, to one of the club cabins on the mountain. In winter the road was never open beyond the 10 Mile Turntable. Depending on the depth of snow, cars could be parked as high as 10 Mile or as low as the 6 Mile Turntable at the Cement Creek road junction. Those without a car could take the train to Warburton and hire a service car to take them up the mountain, or hike up to the ski slopes if they were on a tight budget.

Beyond the 10 Mile 'Turntable' the road was even narrower. In winter it was closed and used as a ski touring route.

However the Warburton Highway was not sealed through to Warburton until 1941, and the road up the mountain was gravel until long after skiers abandoned Donna, so a car journey was not always comfortable.

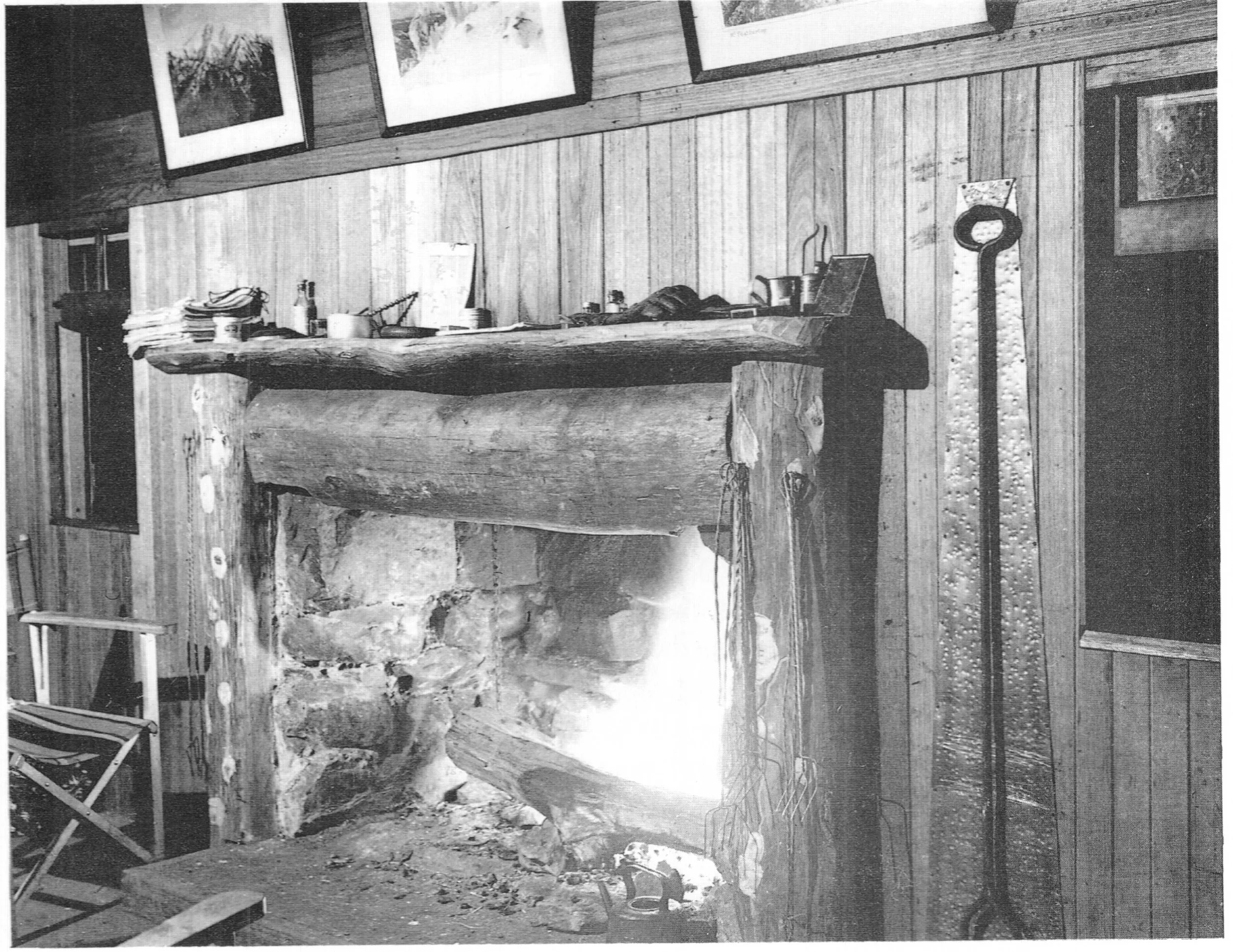

Rock crusher at 8 Mile on the Donna Buang Road circa 1933. The over-used road was rebuilt as an unemployment relief programme during the Great Depression. Later the worn out crusher jaws were salvaged by the University Ski Club and used as a backing for the fireplace of their new cabin.

A picture of the Donna Buang road in the early 1930s shows the unsurfaced road and a narrow bridge. While quite adequate for a minor road, it could not cope with the heavy traffic it received when the mountain became a popular tourist destination.

After the mountain became popular with skiers and other visitors, the narrow road received far more traffic than it was ever designed for and despite maintenance and improvements, wear and tear often made the road rough. As early as 1928, ski traffic reduced it to a muddy bog. The Herald reported that in 1930 ‘skiers… had to leave their cars… and wade through a sea of mud to reach the snow’. At times the heavy traffic was managed by only allowing uphill traffic in the morning and downhill traffic in the afternoon. In his memoirs veteran skier Mick Hull recalled that 'On Sundays [in 1932] we would quit the mountain before 3 pm to be ahead of the crush of returning sightseers'.

Over the 1932 - 1933 summer the dirt road from Warburton to the summit was widened and surfaced with gravel, culverts were built, the car park at the 10 Mile Turntable was improved and one of the heads of Ythan Creek was diverted into concrete pipes under the car park. Some of this work was paid for using unemployment relief funds during the Great Depression of the early 1930s and up to 250 men worked on the project, mostly at subsistence pay rates.

At the same time the Warburton Ski Club built a new foot track from the 10 Mile Turntable to the base of the Main Run to replace the longer original walking route to the summit over a boggy loggers' snig track. This short cut is now overgrown but its route can be followed without too much difficulty by looking for the benching into the hillside on the western side of the 10 Mile Turntable car park. Today most walkers from the 10 Mile Turntable to the summit follow the original route north up Parbury’s tramway to the ridge between Donna Buang and Mt Victoria before turning west to the summit.

The Donna Buang Road near 10 Mile in December 2012, a vast improvement on the 1930s. The tall ash trees over a mid story of myrtle beech is typical of forests on the mountain. Photo © David Sisson.

There appears to have been no snow clearing of the road and heavy snowfalls often meant that cars could not get beyond the Six Mile Turntable at Cement Creek. When this happened, skiers had the option of walking 6 km up the road to 10 Mile or taking the shorter, but much steeper, walking track up the valley of Cement Creek. This track reached the summit from the north east, bypassing the main car park at 10 Mile.

Petrol rationing in the early years of the Second World War caused visitation to the mountain to drop off. But those who saved their petrol coupons for a ski trip were still subjected to media accusations of 'exorbitant' use of scarce fuel for trips to Donna Buang. After Japan entered the war at the end of 1941, petrol rationing was tightened even further and it became very difficult for most people to get to the mountain.

When the war finished, skiers returned to the mountain for a few years but their attention was gradually diverted to the new ski resorts that were developing further from Melbourne and skiers had almost entirely abandoned the mountain by the early 1950s. However Donna Buang remained as popular as ever with hikers and families visiting to play in the snow. So the road continued to carry plenty of traffic, especially in winter.

In the 1950s and 1960s the mountain remained very popular with sightseers, but the road did not receive as much maintenance as it probably should have and it deteriorated to a fairly poor standard. So in the mid 1970's the road was further widened and sealed along its full length. The final section to the summit beyond the junction with the Ben Cairn Road was rebuilt along an entirely new route. To help pay for this work a fee was charged for access during the snow season with a toll booth located just above the 6 Mile Turntable. In 1981 the fee was $1 for cars, $3 for minibuses and $10 for buses. Tolls continued to be charged until about 2008.

In 2009 Parks Victoria officially closed the Cement Creek track without giving a reason and ceased to maintain it. However the track is mostly still in good condition and easily followed except for the upper section of the track before Boobyalla Saddle which has become slightly overgrown with ferns and in places it is difficult to follow where it traverses knee height ferns through woollybutt woodland.

The railway line from Melbourne to Warburton. This 1939 map has been squeezed between the terminus of the electrified suburban system at Lilydale and Warburton in order to fit it on the suburban rail map. At 38 km from the city, Lilydale was exactly halfway to Warburton.

An E-Train at Flinders Street Station. The 'Swing Door' (also known as 'Dog Box' ) electric cars at the front towed the country carriages to the suburban terminus at Lilydale, where a steam engine took over for the second half of the journey. Photographer unknown.

The train

A 2002 recreation of an E-Train of the type that ran to Warburton in the 1930s. The 'Swing Door' (also known as 'Dog Box' ) electric cars at the front towed the country carriages at the back to the suburban terminus at Lilydale, where a steam engine took over for the second half of the journey. Photo © James Brook. Used with permission. Video of the recreated trip.

Another option for visitors to Mt Donna Buang was to catch a train to Warburton after work finished for most people at lunchtime on Saturday. The steeply graded railway with tight curves had been built through the hills as a slow freight line to transport farm produce and sawn timber from the ash forests of the Yarra and Little Yarra valleys, so even passenger trains were restricted to 65 kmh. However, this was still much faster than people could drive on the rough roads of the time.

The railway finally arrived at Warburton in 1900, well after most towns in Victoria. However it was immediately successful, partly as it opened the upper Yarra Valley to closer settlement, but mainly because it allowed the tall forests of woollybutt and mountain ash to be harvested economically. Hundreds of kilometres of light tram lines were built into every valley in the areas around Warburton and Powelltown to transport logs to dozens of sawmills and to then move the sawn timber to railway stations such as Yarra Junction and Warburton. In the 1920s it was asserted that Yarra Junction was the second busiest railway station in the world for loading sawn timber, (after a location in Washington state USA). While claims like that are impossible to verify, it is certain that vast amounts of sawn timber were transported along the railway in the first half of the 20th century and some of the timber tram lines on Donna Buang that fed the sawmills were used as access routes by early skiers.

Warburton station was only the passenger terminus. Being built into the side of a steep hill there was no room for a turntable and it was awkward to load sawn timber and other freight. So soon after the line opened it was extended by 1 km to La La Siding, a large flat area next to the Yarra River where freight wagons could be loaded more easily. Passenger trains never went to La La, although steam engines did continue on their own to the La La turntable so they could be turned before coupling to the other end of the train for the return trip to Lilydale.

Most passenger trains on the Warburton line were 'E-Trains'; a type of country train service for branch lines that didn't run too far beyond the electrified suburban network. The carriages bound for the upper Yarra Valley were hauled by electric 'swing door' suburban carriages as far as Lilydale where they were detached and a K or D3 class steam engine took over. Usually two carriages went to Healesville and two to Warburton. However special steam hauled trains often ran all the way from Melbourne to Warburton, especially during the peak summer tourist season. In 1939 a return train ticket from Melbourne to Warburton cost 8/7.

A J class steam engine at Warburton station in 1964, a year before the railway line closed. The scene was largely unchanged from 30 years earlier. Photo © Weston Langford.

On arrival at Warburton, most train travelers bound for the snow paid 3 shillings return for an eight seat ‘service car’ to take them as far up Donna Buang as possible. Depending on snow conditions, this could be lower on the mountain at the 6 Mile Turntable at Cement Creek or higher up the mountain at the 10 Mile Turntable. Then they walked to the ski slopes or to one of the club-owned cabins if they were planning to spend the night there. Most of the club cabins were a short walk from the 10 Mile Turntable.

However some energetic (or thrifty) skiers chose the steep walking track starting at Martyr Road that is still used today. A few especially intrepid characters also walked up the route of Parbury’s Mill cable-hauled tramway 300 metres to the west, which crossed the summit road at the 10 Mile Turntable. The top section of this haulage is still used today as the walking track heading north from 10 Mile, but it originally lowered timber all the way to a sawmill at Millgrove railway station on the Yarra River.

In summer buses transported tourists all the way to the summit observation tower.

After the Second World War, car ownership increased rapidly and with the road sealed as far as Warburton, fewer people took the train. An attempt to revive passenger traffic was made in early 1958 with the introduction of more comfortable 40 seat Walker railcars, but this did little to reduce the decline in passenger numbers, so with few people using the train, passenger services were withdrawn in 1964.

Haulage of sawn timber and agricultural produce had been the mainstay of the line but this freight traffic also began to decline with much of the timber being harvested in the preceding 50 years and even the earliest coupes to be logged had not had time to regrow. Increasingly widespread ownership of trucks after the war meant that a lot farm produce now travelled by road. However traffic on the Warburton railway was sustained by the construction of the Upper Yarra Dam from 1948 to 1957 and vast amounts of concrete and other construction materials were railed to La La goods siding 1 km beyond Warburton station. But with the dam complete and diminishing timber and agricultural traffic, there was no way to justify the expense of keeping the line open and it closed in 1965.

After the line was dismantled in the 1970s, the route of the Warburton railway lay unused until it was converted to a gravel path between 1996 and 1998. The more scenic sections of this path remain popular with walkers, cyclists and horse riders today.

A few fragments of the old railway survive. The Yarra Junction station has become a busy museum operated by the Upper Yarra Valley Historical Society while the rusting remains of the Warburton railway turntable are at the former La La railway goods yards, about a kilometre east of the site of Warburton station.

A 1920s style charabanc. Source Museums Victoria.

Buses and service cars

Most visitors drove to the mountain themselves or took the train to Warburton. Others took a railways bus which ran at times of high demand when no train was scheduled. The Victorian railways introduced bus services in 1925 in response to increasing competition from privately operated buses and as early as 1928 a bus operated by the Victorian Railways was scheduled to arrive at Warburton at 6.30 on Friday evenings.

A Pioneer Tours trip to Mt. Donna Buang. Photo supplied by Vivienne Worthington.

The government owned railways dealt with competition from privately run buses by running bus services of their own, but also through lobbying to restrict the operation of competitors. From 1924 the state parliament passed four acts specifically applying to bus operators. The most effective in thwarting competition with the railways was the Motor Omnibus (Urban and Country) Act of 1927. The four acts were consolidated and refined in the Motor Omnibus Act 1928. Section 38 (a) specified restrictions on bus services that might damage roads or compete with trains and trams. While a few bus operators elsewhere in Victoria (notably Reginald Ansett) managed to run services on the edge of the law by exploiting legal loopholes, these acts largely eliminated bus competition with the railways in the years before the Second World War.

An early Pioneer snow tour. Photo supplied by Vivienne Worthington.

The legislation defined a 'motor omnibus' as a vehicle able to carry at least six passengers, so the railways did not have a complete monopoly on public transport to Warburton and a few service cars continued to run from Melbourne, however the fares were expensive. One company did manage to get a license to run a small 14 seat bus to Warburton from Melbourne in the late 1920s but the service only lasted a few years. So most people without their own cars continued to rely on the railways to get to Warburton.

Beyond Warburton, there were no government owned railways, so privately run transport was less hampered by the Motor Omnibus Acts. In the 1920s before modern style buses reached the Upper Yarra, charabancs were used. Essentially these were stretched versions of the cars of the time with four rows of seats and four doors along each side.

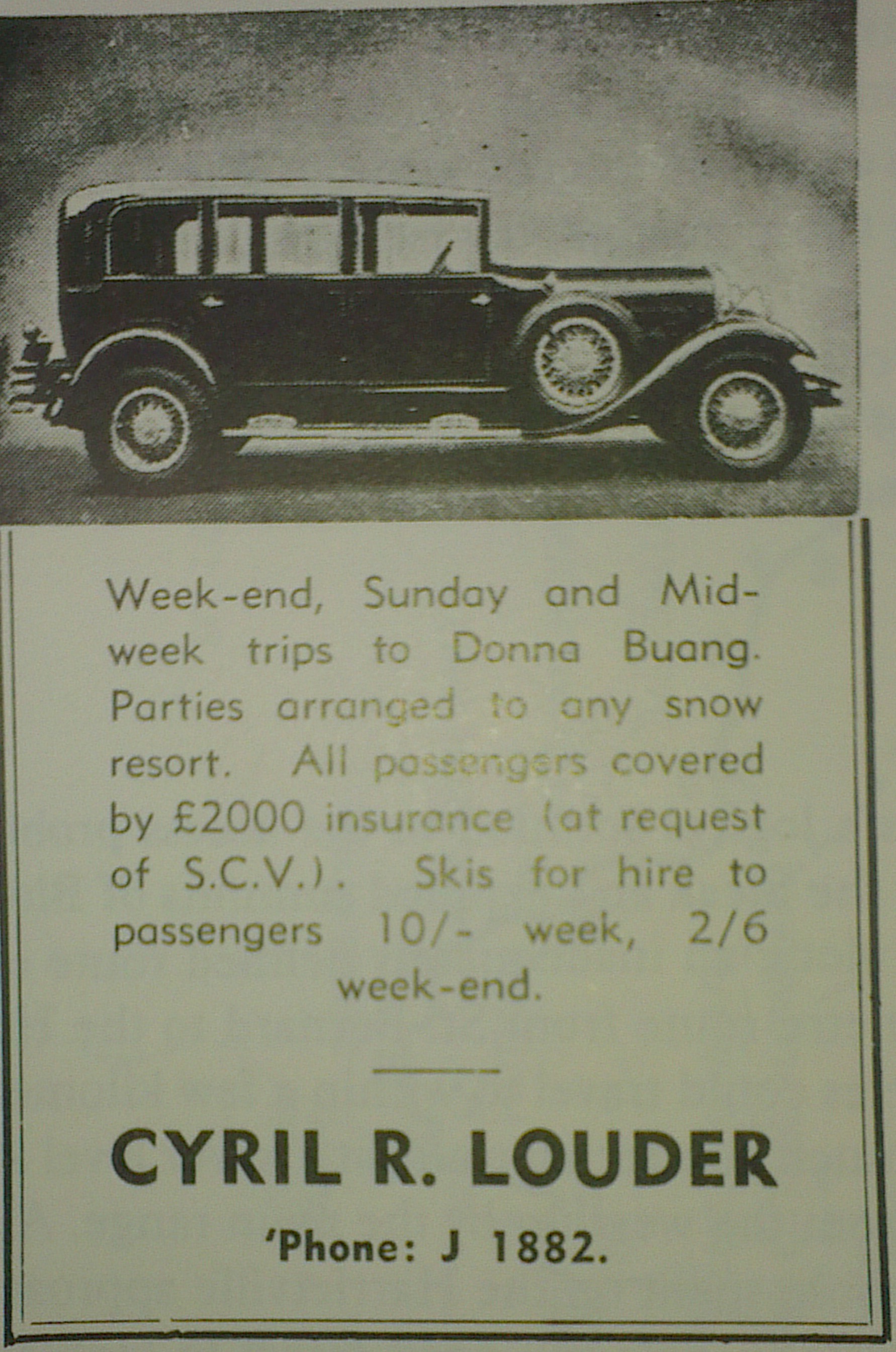

Ski Club of Victoria. Yearbook 1934. p. 158.

In the 1930s as many as four proprietors at a time operated service cars from Warburton. Their business was a mixture of private rentals, scenic tours for tourists staying at guesthouses, mail and passenger contracts for places further up the Yarra Valley such as McMahon's Creek, McVeighs Hotel and even all the way to Woods Point, which was still a sizeable town at the time. Of course in winter there was also the shuttle up to Mt Donna Buang. Most of the vehicles were large semi-luxury cars but one business had 14 and 24 seat REO buses in addition to their cars.

From 1925 until at least 1929, Pioneer Tours ran day trips to the snow at Donna Buang. Initially they used Nash vehicles but from the late 1920s they moved to Studebakers and Packards. The photos show a 'cavalcade' of up to seven cars that made the Donna Buang run for Pioneer.

Later, dedicated transport for skiers was introduced. The Ski Club of Victoria organised car pooling for members of their club in the early 1930s, charging 11 shillings for a return trip from Melbourne. From 1936 all city based skiers could utilise a hire car service operated by Cyril Louder. Louder ran an eight-seat Buick fitted with ski racks and also charged 11/- for the trip to Donna Buang.

Alternately people could hire the Buick or a Hudson car from Louder and drive themselves for 8d per mile (1.6 km). Trips were run to any snowfield that clients wanted to get to and there are stories from the time of Louder's frequently overloaded cars getting bogged in some of the most remote locations in the mountains.

1949 map of Mt. Donna Buang. © Stuart Brookes, used with his permission.

5. Buildings and accommodation

Accommodation in Warburton

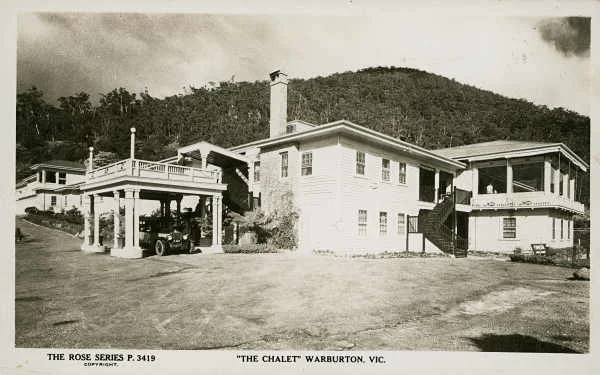

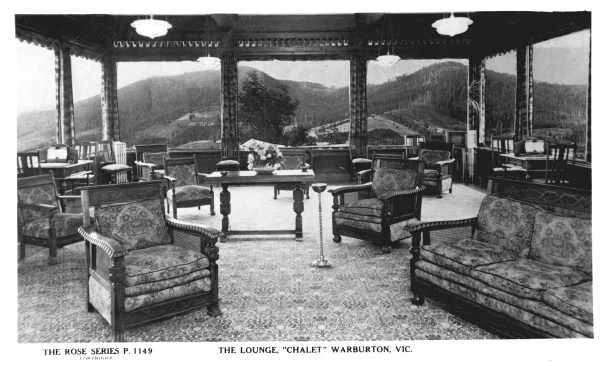

Warburton started developing as a tourist destination with the arrival of the railway in 1901 and from the 1920s there was an increasing amount of tourist accommodation in town catering to the summer market. Most accommodation was in guesthouses such as the huge, 250 bed, Warburton Chalet and Green Gables, which was especially popular with members of the Ski Club of Victoria. Other clubs and groups had their own favourite guesthouses. The Rover Scouts, who were usually on a fairly tight budget, stayed in a run down house for a nominal fee. Despite the sizable tee-total Adventist population in Warburton, there was also a hotel in town.

Green Gables was popular with SCV members before the club built a cabin on Donna

Guesthouses have largely disappeared today, but in the first half of the 20th century they were the most popular type of holiday accommodation. They ranged from small establishments with a few rooms run something like a modern B & B, right through to Phil Mayer's large and comfortable Warburton Chalet.

All featured communal lounges or 'parlours' where guests could relax and socialise. The rooms in most guesthouses had thin walls and were fairly small and basic by todays standards. Few places had ensuite bathrooms although some had a hand basin with a cold water tap in the bedrooms. Perhaps the nearest modern equivalents would be a bottom end ski lodge or a well run and cleaner than average backpackers hostel that includes meals in the tariff. That may sound rather bleak and basic for holiday accommodation, but living standards were lower in those days and people placed less importance on privacy, so guesthouses were quite popular.

With interest in skiing increasing by the late 1920s, proprietors of accommodation houses in Warburton took note and advertised to skiers in order to fill their rooms in the winter low season. The 1934 year book of one ski club features 22 advertisements from Warburton businesses. The Alpine Retreat Hotel at Warburton even offered a dedicated lounge room for the exclusive use of skiers.

But while there was plenty of accommodation available in town, Warburton based skiers faced a long and often difficult climb up the mountain each day, so attention turned to providing accommodation closer to the ski slopes.

Loggers huts on Donna Buang, winter 1924. Photo Weekly Times.

Club cabins

By the late 1920s Donna Buang was becoming increasingly popular as a weekend ski destination and in 1929 the mountain had 'continuous snow for almost four months'. At the time many skiers were content with occasional day visits from Melbourne or commuting up the mountain from accommodation in Warburton.

Events at Donna Buang received fairly good coverage in Melbourne daily newspapers. Extract from an article in The Argus.Saturday 14 July 1934. p. 10.

However travelling from Warburton each day could be slow and difficult. More importantly, it occupied time that could be better spent skiing. So attention turned to providing accommodation for skiers on Donna Buang. While groups from many clubs such as the Australian Women's Ski Club and even the distant Benalla Ski Club visited the mountain, from 1930, four clubs decided to build there. Because the club cabins were designed for relatively short stays and the mountain was not remote, they were not as large or as comfortable as commercial ski lodges of the time on more distant mountains, although they were a definite step up from the logging, miners and cattlemen’s huts that some skiers were used to.

The SCV Cabin on Mt Donna Buang from the walking track which still passes the ruin today

Many pioneering skiers had stayed in basic huts in the mountains of north eastern Victoria and places such as Cope Hut on the Bogong High Plains (1929) and Boggy Creek Hut on Mt Buller (1934) were built specifically for skiers. In addition six relatively comfortable commercial ski ‘chalets’ had been built: The Buffalo Chalet (1911), Rundell’s Alpine Lodge at Flour Bag Plain (an old mining hotel near Dinner Plain reopened in 1921), Hotham Heights (1925), the Feathertop Bungalow (1925), St Bernard Hospice (renovated and reopened 1925) and the Mt Buller Chalet (1929). All were successful and most were booked out months before the ski season started. So it made sense to build accommodation on Donna Buang too.

The small ski lodges on Donna Buang (or cabins as they were often called) were built by clubs on ‘permissive occupancy’ leases. In the past this was a fairly common form of tenure on Crown land in Victoria whereby an individual, club or company was granted permission to build in return for a modest rental, typically £1 per annum for the cabins on Donna. Many early ski lodges were built on PO's, right through to the 1960s. In theory PO lessees could be evicted at short notice without compensation, but this never happened to a ski lodge in Victoria until the 1980s when a controversy erupted at Mt Buller over the remaining permissive occupancies being replaced by more conventional leases.

The cabins appear small and fairly basic by today's standards and all were some distance from the road. Typically they slept over a dozen people in bunks on the edge of the main living area, with one cabin having space for more mattresses in an attic. Pit toilets were outside and washing facilities were limited. But skiers were a hardy lot in those days. In the 1930s there was only one ski lift in Victoria, so skiers were used to climbing hills and the cabins on Donna were a great improvement on the miners' and cattlemen’s huts they often stayed in at other ski destinations.

Four clubs built small lodges on the mountain. This made Donna the pioneer of the club lodge based resorts that developed from the late 1940s across Australia and New Zealand. Elsewhere, Australian ski fields in the 1930s featured isolated commercial lodges (such as the Buffalo Chalet) or individual club huts and lodges (the first was the Ski Club of Tasmania's 1927 hut that still stands at Twilight Tarn near Mt Mawson).

Donna Buang's pioneering example of a group of club lodges on a single mountain, with members cooperating to improve ski slopes and amenities was the template for the way most Australian ski resorts developed after the Second World War. CSIR, the first club lodge built at Mt Buller after the war was smaller and more basic than some cabins at Donna, but it was the first of hundreds of ski clubs to build on that mountain in the decades that followed. While most early ski resorts are now large commercial operations, the seven clubs with lodges at Mt Mawson near Hobart still hold volunteer work parties every summer and run their 'club field' in a way that would be familiar to skiers at Donna Buang in the 1930s.

However, unlike many other early ski destinations, Donna Buang never developed a proper ski village. Like most later ski areas, the first cabins were not all close to each other. At Donna, the University Ski Club and the Ski Club of Victoria were near the base of the ski runs to the east of the summit, but the Melbourne Walking Club and the Rover Scouts were some distance away in opposite directions. At other resorts, later development filled in the gaps between the original dispersed buildings, (at Mt Hotham the first four lodges were also 3 km apart), but there was no later development at Donna Buang.

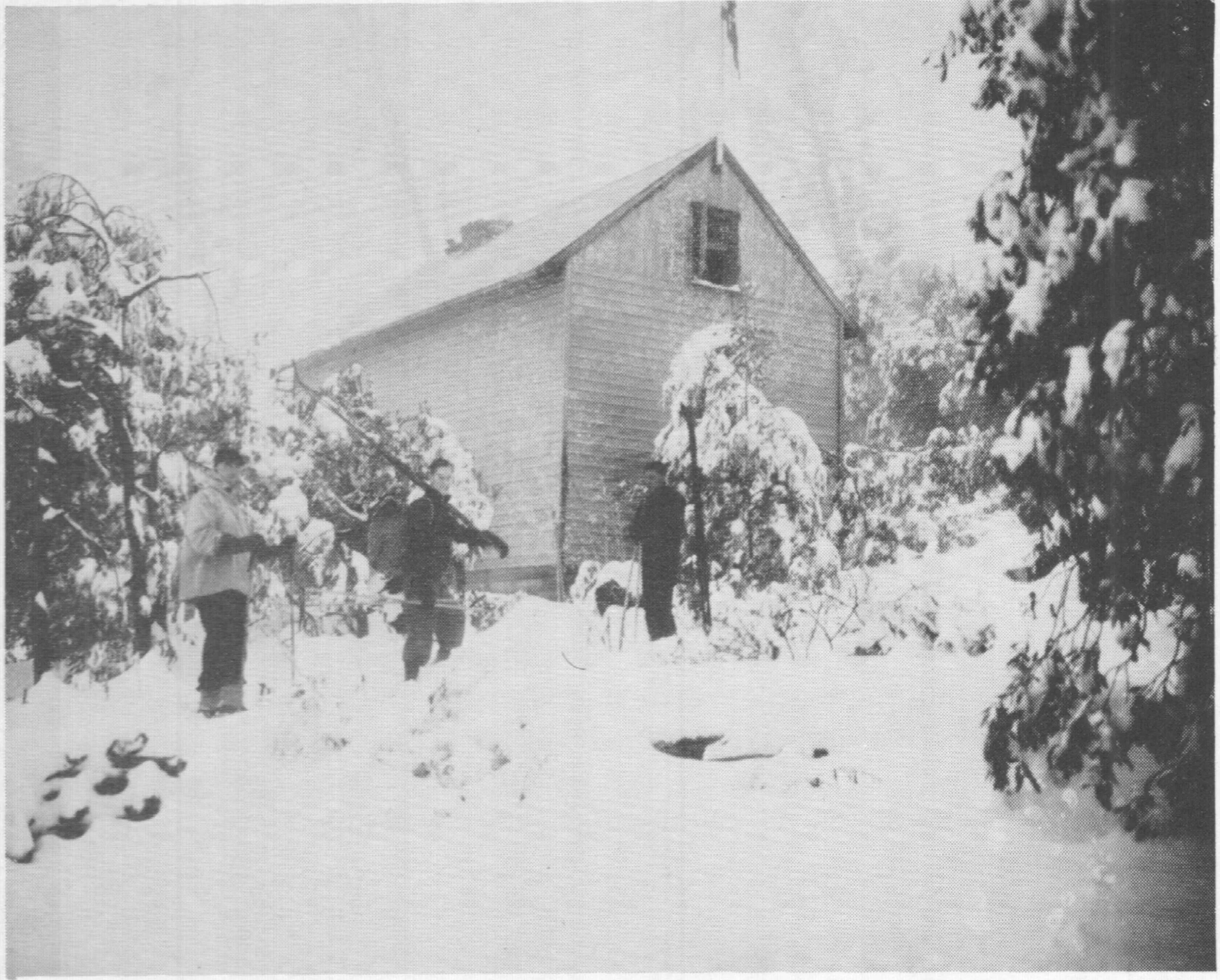

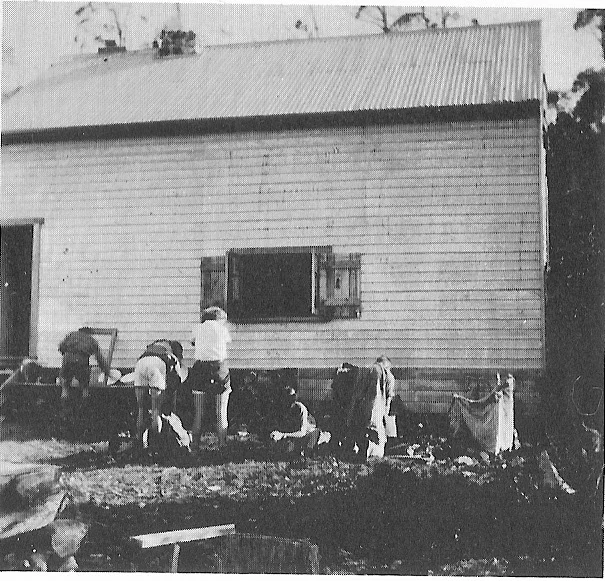

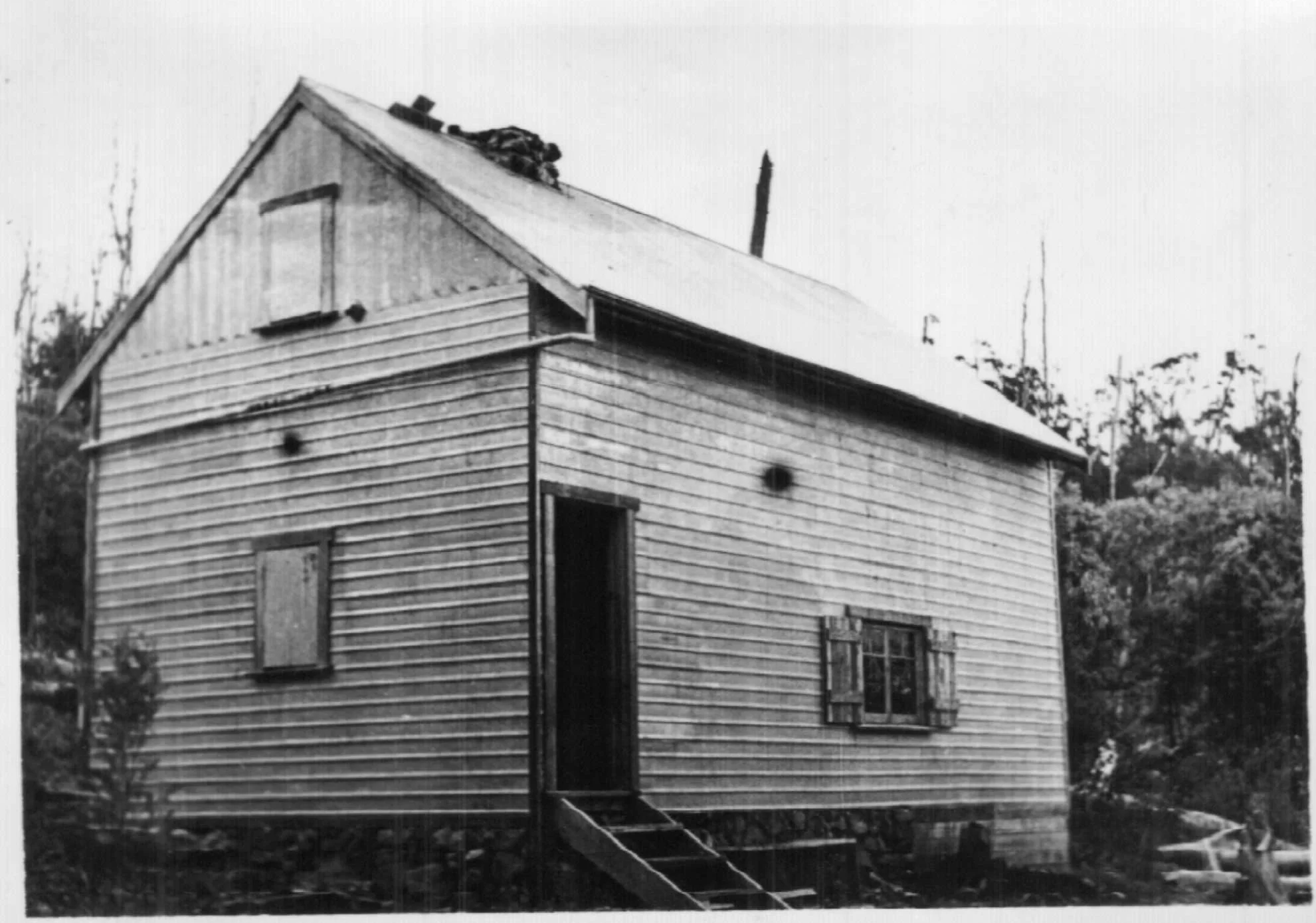

A 1934 work party at the first Melbourne Walking Club hut. Used with permission of MWC.

Melbourne Walking Club. The Walter E. Briggs Hut

Founded in 1894, the Melbourne Walking Club is a hiking club for men. It thrived in the early twentieth century and Donna Buang became an increasingly popular destination for walks by the club in the 1920s. Many club members were also involved in the pioneering days of recreational skiing, so it is not surprising that in 1929 Bill Waters and Chris Bailey persuaded the club to build a hut on Donna Buang. While the hut was built with skiers in mind, it appears that it was also intended that it would be used in summer as well.

The rebuilt Melbourne Walking Club hut on the same site in 1950. Used with permission

A site 1 km from the summit was selected in April 1930 and a permissive occupancy lease was apparently obtained. Quotes were obtained from Gardner Constructions for materials to build a 4.8 metre wide by 6.5 metre long hut delivered to Warburton Railway Station for £52/10/- or a 7.6 metre long hut of the same width for £57.

It appears that the original hut was built by club members, but paid for by the Forests Commission with an agreement that the club would donate £25 towards costs if the shorter hut was built or £30 if the longer hut was chosen. A Forests Commission file on the hut states ‘The… Club are sharing in the cost [of the hut] and their members have undertaken to erect same’. But there is no indication of why the Forests Commission would have paid part of the cost of what appears to have been a private club project. It is possible that it might have been intended to use the hut as accommodation for fire watchers in the summer period, although neither surviving Forests Commission nor Melbourne Walking Club records confirm this and after the war, only the University Ski Club and Ski Club of Victoria cabins were rented as accommodation for fire watchers. By 1960 it appears that the FCV were thoroughly confused about the huts status ‘It is not known what the origins of the arrangements are, but it appears that the hut may have been erected by the commission for the club. There is no permissive occupancy license. In the past five years no departmental use has been made of the hut’. An addendum in pencil adds ‘no charge for rental ever made’.

So it looks like the reason why the Forests Commission paid half the cost of a club hut has been lost, but whatever that reason was, it appears that the club ran the building as if it was entirely their own. An opening ceremony was held in December 1930 and in 1933 it was named the Walter E. Briggs Hut after the incumbent club president.

The clubs optimism about the mountain’s ski potential was confirmed when a work party was almost snowed in on Anzac Day 1930. The eight bed hut proved popular and volunteer work parties improved it over the years, painting it, fixing the water supply and rebuilding the fireplace to help it draw better.

The cabin was initially saved from the Black Friday wild-fires on 13 January 1939, but was subsequently burnt by windblown embers a few days later, after the firefighters had left.

Happily the building was covered by the Government Insurance Office and a £200 payout financed the Forests Commission to construct a new wooden hut from December 1940 to January 1941. The internal fittings were at the club's expense.

With wartime petrol rationing, it usually wasn't possible to drive to the mountain in the early and mid 1940s, instead MWC members reported that it took them up to four hours to walk from nearby railway stations to the hut if they were carrying skis and heavy packs up the mountain for a weekend. After the war, outbuildings such as a new toilet and woodshed were built as the hut became more widely used. In the latter part of the 1940s, the club ran bus trips to the hut and hired it to groups of Rover Scouts.

Perhaps because the Melbourne Walking Club was not a dedicated ski club, their accommodation on the mountain continued to be popular with members into the 1950s, well after most skiers had abandoned Donna Buang. The Melbourne Walking Club had enjoyed their experience with skiing and as Donna declined as a ski destination, they built another ski lodge at Mt Buller which lasted from 1951 to 1990, before it was replaced. This newer lodge at Mt Buller still provides accommodation for members of the states equal oldest walking club today.

Plan for the 1940 rebuild.

Click to enlarge.

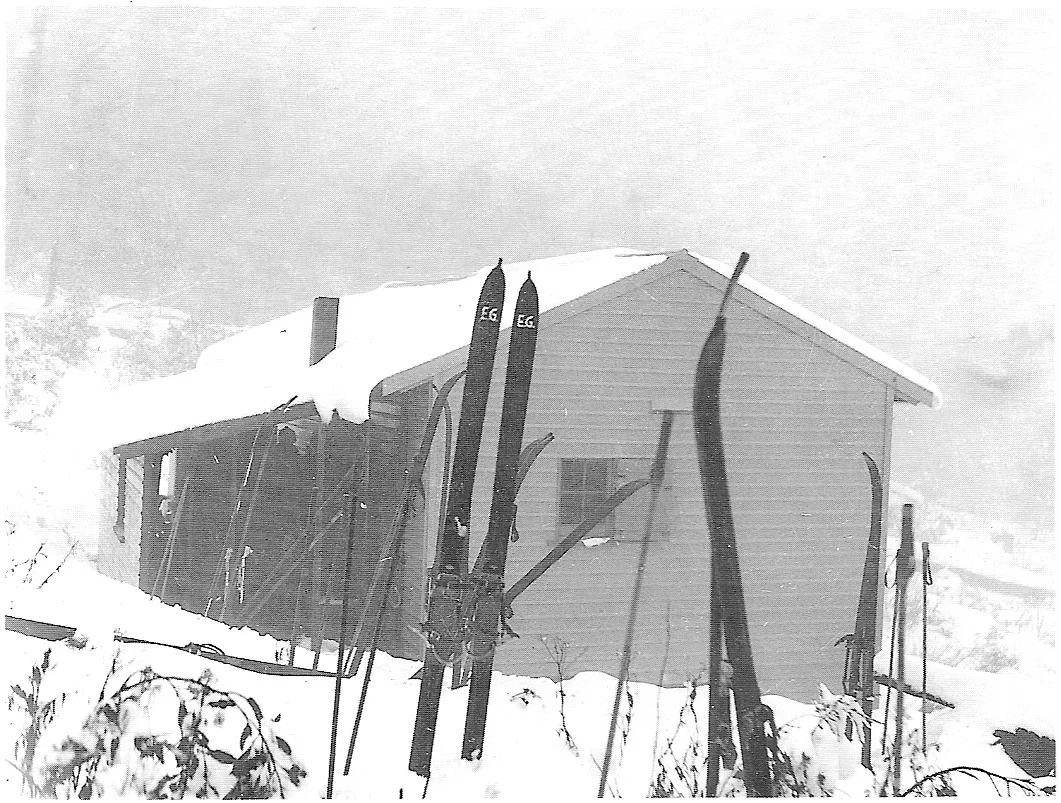

Above: The University Ski Club's cabin at Donna Buang with the 1935 porch.

Below: A view of the rear showing the chimney.

University Ski Club cabin

The University Ski Club was granted a permissive occupancy lease on the mountain for £1 per year in April 1934. Once the lease was granted, the club wasted no time and began to build immediately. A Warburton builder was employed to build a 4½ x 10½ metre iron clad hut with a stone fireplace. The snow arrived late that year, so building could continue into early winter and up to 11 carpenters at a time were working on the site. The lodge was quickly completed and was formally opened on 8 July 1934, making it the first lodge owned by a ski club in Victoria, narrowly beating the SCV's cabin at Donna Buang and their Boggy Creek Hut at Mt Buller.

The building was designed by Malcolm McColl who went on to design Cleve Cole Hut on Mt Bogong in 1937 and he became one of Victoria's leading snow country architect in the years after the Second World War.

The hut was paid for by 17 club members who each provided £12, about $1,200 at 2018 values. In return they were guaranteed a bed for the next 12 years, when the cabin would revert to the club. The rights to a bunk could be sold, and several transfers took place. For others the tariff was a shilling for a week night or 3/6 for a weekend.

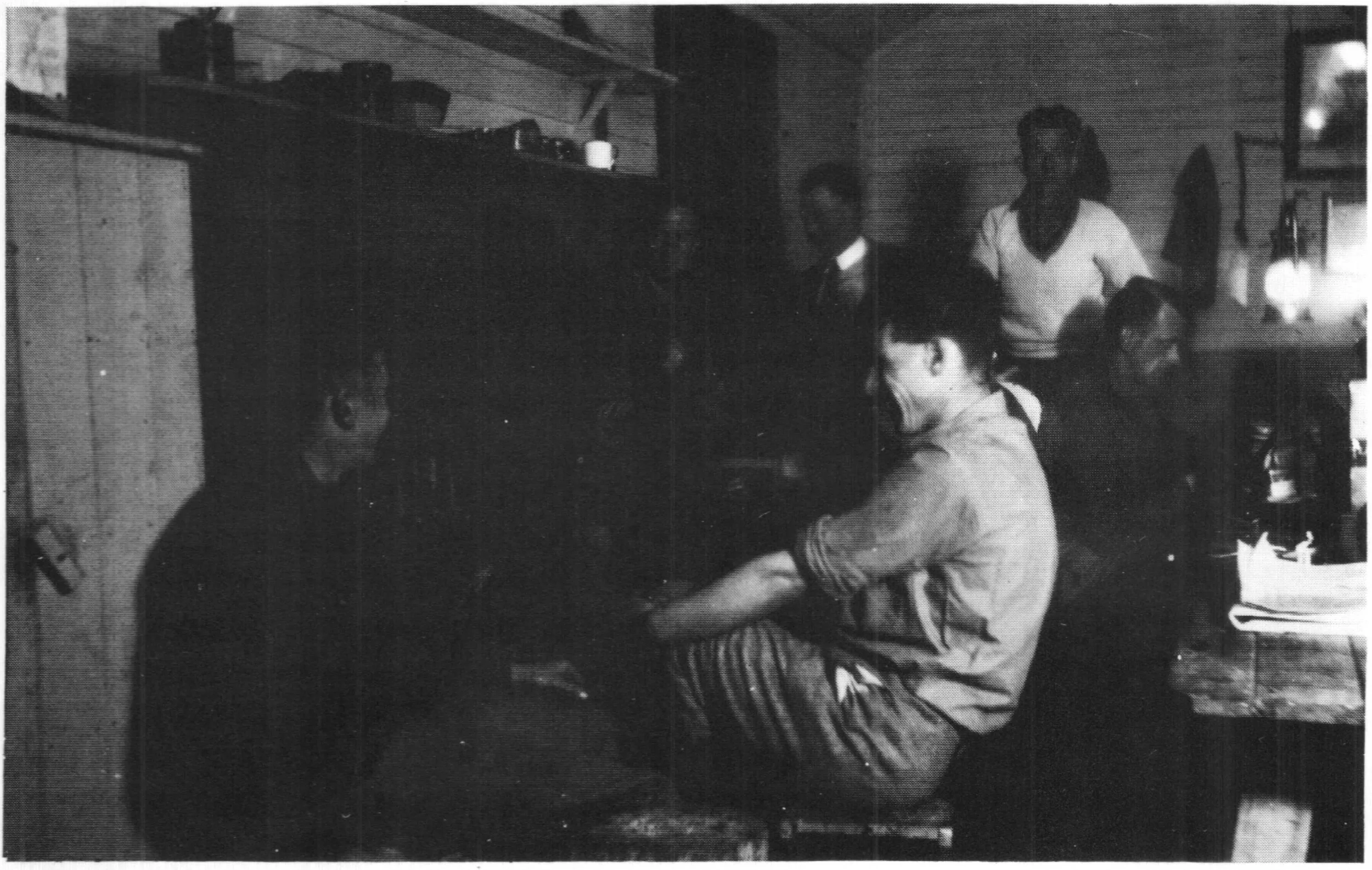

The University Ski Club cabin fireplace in action. Photo Warrand Begg.

The main room was lined with locally milled, varnished tongue and groove hardwood and decorated with framed photographs of other skiing locations such as Mt Buller. It had six bunk beds along the walls. Additionally there was a kitchen area and a small room with five beds. Men usually slept in the main room and women in the smaller bedroom. The nominal capacity of the hut was 17, but at times many more slept there. In 1935 a 3½ x 2½ metre entrance porch was constructed with material salvaged from derelict logging huts nearby.

The cabin was managed by a three person committee comprising the club president plus a male and a female elected by those who had 'subscribed' to a bunk. It was maintained by volunteer summer work parties and was popular with club members in the pre-war years, albeit with a slight decline in the late thirties.

The U.S.C. cabin survived the 1939 fires which burnt three huts on Donna Buang as well as three commercial ski lodges near Mt Hotham. While Hotham Heights was rebuilt before the outbreak of the Second World War, the loss of the large Buller Chalet to fire in 1942 compounded the shortage of ski accommodation. Even if skiers could get a booking at the Buffalo Chalet or the rebuilt Hotham Heights, petrol rationing and restrictions on civilian rail travel meant it was difficult for them to get there. This shortage of ski accommodation ensured that the USC cabin remained fairly popular throughout the war despite increasingly severe petrol rationing.

Scene after the cabin was moved to Buller. The tank has since rolled to below the chimney

Wartime shortages meant that worn out or decayed fittings could not be replaced; only 11 mattresses remained serviceable by 1944, but that didn't stop the cabin being full for much of that winter. After the war, the hut was renovated and fees were reduced to 2/6 for a weekend and 5 shillings for a week. Bookings were high in the bumper 1946 season, but declined from 1947. In 1948 and 1949, they were especially low. This reflected a couple of poorer than average ski seasons, but also the changing orientation of skiing in Victoria towards the higher mountains to the north east.

The author at University Ski Club chimney in March 2013 after a four hour search for it. The chimney is all that remains today after the cabin was shifted to Mt Buller in 1950. Photo © Blair Hamilton.

The U.S.C. built its own lodge at Mt Hotham which was open for the 1949 ski season. It cost a whopping £2,740. Meanwhile at Mt Buller, a small squatter village of illegal shanties and caravans hidden in the scrub had sprung up after the 80 bed Buller Chalet burnt down in 1942. The authorities at the Forests Commission realised some sort of administration was needed at Buller and from 1947 permitted a few clubs to build on sites of their choosing. They were overwhelmed with further applications and in the 1948 - 49 summer, the Forests Commission opened up a formal subdivision on the mountain. All of the 22 extra sites were immediately taken up and there was a strong demand for more from other clubs and groups that had missed out.

The University Ski Club was one of the successful applicants for a site on Mt Buller, but they were overstretched by the cost of their Hotham lodge and restricted by post war shortages of building materials. However they were required to build quickly or they risked losing their prime site. Faced with this dilemma, the U.S.C. turned to the Donna Buang cabin which was no longer meeting the accommodation needs of its members.

The December 1949 issue of Ski Horizon magazine reported that the U.S.C. was 'interested in selling their Donna Buang Cabin'. Apparently there was no interest from the ski community so they considered selling the cabin to the Forests Commission, as the cabin had been hired as accommodation for fire watchers in summer. However the 'suggested' price of £140, or one twentieth of the cost of their Hotham lodge, was far below what the USC thought the Donna Buang cabin was worth.